By R.W. Julian

The history of seizures of coins and gold is a checkered one and dates back to the 19th century. The first tentative steps in this direction came in the late 1850s when certain Philadelphia Mint employees, with unauthorized access to the dies for the 1804 dollar, struck off several specimens for sale to wealthy collectors.

Many readers of COINage are aware of the recent public disputes over the ownership of the 1933 $20 gold pieces. The matter wound up in court, and the government eventually prevailed, seizing the coins from the Langbord family. Many people considered the seizure as unjust and believed that the coins rightfully belonged to the Langbords.

Coin Seizure History

Although Mint Director James Ross Snowden had himself been using old dies on hand to strike rare coins for collectors, he had not restruck the 1804 dollars and had used his pieces to build up the coin collection at the Mint through trade and sales. Snowden took strong exception to the unwanted competition and sought out the 1804 dollars that had escaped the Mint without his permission. He managed to buy back most of them, but a few escaped detection and eventually found their way into mainstream numismatic auctions. These are known today as Class III 1804 dollars.

For some years after 1860, no one seemed worried about pattern coins that may have left the Mint without full documentation. It was not until June 1887, when the collection of former mint director H.R. Linderman was cataloged for sale by Lyman Low, that problems arose. The Treasury demanded that certain pattern and experimental pieces be returned, as there was no authorization for such pieces leaving the Mint. In particular, the government claimed that Dr. Linderman had no right to possess certain coins struck in aluminum.

The push to seize the coins seems to have come indirectly from the office of Mint Director James P. Kimball. In April 1886, he had asked Philadelphia Mint officials for a set of U.S. coins in copper, as had been done in the past for other officials, but this time the Mint refused to cooperate, which apparently irritated Kimball. The appearance of the Lyman Low auction catalog in June 1887 allowed Kimball to retaliate against the estate of former Director Linderman, and he was able to get the sale stopped.

Case by Case Consideration

Negotiations then ensued between Linderman’s widow and the Treasury, the result being that some of the disputed pieces were allowed to be sold along with the rest of the collection. In February 1888, the Scott Stamp & Coin Company sold the Linderman holdings at public auction. Twelve lots from the June 28, 1887, aborted Lyman Low sale were withdrawn, having been seized by the Treasury. The complete set of cased aluminum coins for 1868, lot number 55 of the Low catalog, for example, was among those items seized.

The next dispute over special coins that had left the Mint under less-than-perfect circumstances came in 1909 when William Woodin, later President Franklin Roosevelt’s Treasury chief, bought two $50 gold patterns that had been struck in 1877. They were obtained from former Mint official A. Loudon Snowden; he had them struck at his own expense and kept them until the sale to Woodin.

For reasons that are obscure at this late date, there was an uproar over the sale because

(Images courtesy Heritage Auction).

the national coin collection, then at the Philadelphia Mint, did not have specimens in gold of this pattern. There are two varieties, with minor differences.

In 1910, Woodin agreed to donate the two gold coins to the national collection and was in turn reimbursed by Snowden with a number of pattern coins, many of which were until then unknown to the numismatic world.

Trade Dollars In the Spotlight

At this point, there was again a period when nothing happened in the world of seizures. Oddly enough, there had been and would be instances when the government could have acted but did not. Perhaps the first of these was the appearance in 1908 of the 1884 and 1885 Trade dollars, unknown until that time. No one seemed to get upset about these newly discovered coins, and the Treasury took care of the matter as it ought to have been handled – by doing nothing.

In 1919 came one of the more famous instances of coins leaving the Mint in a strictly illegal manner. The 1913 Liberty Head nickels were struck by an employee, said to have been Samuel Brown, and smuggled out of the Mint. They were later sold to famed collector Colonel E.H.R. Green and remained in that collection until Eric Newman purchased all five of the pieces. The set was later broken up.

As the discovery of the 1913 nickels was widely reported in the numismatic press in 1919, Mint officials were well aware of what had happened. Yet they did almost nothing, except to prepare a short pamphlet discussing the matter. The pamphlets were sent to any person inquiring at the Mint Bureau about the 1913 nickels. The general attitude of the Bureau was that it was a minor matter, not worth the time and trouble to do anything.

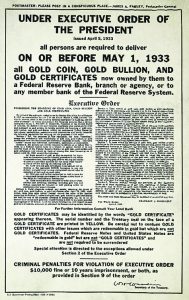

The year 1933 was a special one for numismatics. President Franklin Roosevelt issued an order, under an obscure World War I law, compelling citizens to turn in their gold coins to the government. Some allowance was made for numismatic items, but on the whole all was to be turned in. Wealthier citizens hid their gold or shipped it to Europe for safekeeping, but in general the public did as it was told and great quantities of gold coins were surrendered to the Treasury.

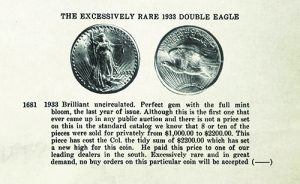

The most interesting aspect of the 1933 gold seizure order was the coinage of double eagles ($20 gold pieces) in that year. By 1937, they were being openly bought and sold in the numismatic marketplace, and no one seemed concerned, especially the Mint Bureau.

Inquiries Lead to Investigations

One of the 1933 double eagles was offered for sale in a late March 1944 Stack’s auction of the James W. Flanagan collection. A reporter, who also happened to be a collector, wrote the Mint Bureau asking how many had been released. The query fell on the desk of assistant director Dr. Leland Howard, who investigated the matter and could find no record of such coins being paid out to the public.

Dr. Howard, through the Secret Service, demanded that Stack’s hand over the coin to the

government, and this was done. Over the next few years, several more 1933 double eagles were seized and melted. The owners were not reimbursed. Well-informed numismatists knew that other such coins were in existence but did not let Dr. Howard in on the secret.

Until the early 1970s, little was then heard about illegal coins and government seizures, but a series of tests on the lowly cent revitalized the subject. Under Mint Director Mary Brooks in 1974, there were tests of aluminum for cent coinage due to the rising cost of copper. In 1982, the cent composition was changed to copper-coated zinc, which is still with us today.

Some of the aluminum strikes were furnished to a variety of people to examine, including members of Congress, and not all of the pieces made their way back to the Mint vaults. For some years, there was a hue and cry over the matter, and a few more were perhaps recovered, but there were no seizures by the Secret Service. About a dozen pieces are said to be missing, however, and subject to confiscation by the Secret Service.

Aluminum Cent Structure

In 2014, an aluminum cent struck at the Denver Mint in 1974 was discovered. A dozen or so had supposedly been minted. One of these had been given to a Mint employee at that time; his son inherited the piece and planned to sell it, but the modern philosophical heirs of Dr. Howard learned of the situation and brought the full weight of the federal government down on the hapless owner. In due course, he was forced to surrender the coin.

In the meantime, the 1933 double eagle matter came alive. A British coin dealer brought one of these coins into the United States in 1996 to sell to another dealer, and he found himself looking at the drawn guns of six Secret Service agents. They seized the coin, and they arrested the two dealers involved in the planned transaction. The dealers were soon released but the coin was kept, subject to a court trial to determine ownership.

Just before the planned trial in January 2001, the Treasury lawyers decided that they might lose the case, due to planned numismatic testimony by defense witnesses, and offered to settle. It was no doubt a galling experience for the Treasury lawyers, but, nevertheless, a compromise was reached, and the coin sold at auction in August 2002, the proceeds being split between the British dealer and the government.

In 2003, the Langbord family found 10 more of the 1933 double eagles in a lock box. The coins had once been owned by Israel Switt, a New York jeweler who is known to have sold some of these double eagles to collectors in the 1930s.

Impact of Consideration

This time around, the Treasury was determined to avenge its embarrassing failure in 2001 over the single 1933 double eagle. For apparent legal reasons, the lawyer for the Langbords turned over the 10 pieces to the Mint for “authentication,” but the Mint simply kept the pieces and refused to return them to the rightful owners on the specious grounds that stolen property was being recovered.

A lengthy series of court battles ensued, and the Treasury lawyers were eventually

victorious in August 2016. Most numismatic observers thought that the Langbords should have won, but the judges thought otherwise. How much the Treasury and Mint spent on this assault on common sense has never been disclosed, but it was substantial and a waste of taxpayer funds.

In the earlier years, the Mint was not all that interested in pursuing questionable coins, but today the institution has signaled, with the 1933 double eagles and 1974–D aluminum cent, that collectors need to be wary of the lawyers in this branch of the federal government.