By Steve Voynick

Editor’s Note: This is the first of a two-part series. Enjoy part II >>>

Gold rushes had a significant impact on American monetary policy and coinage during the 19th century. Together with a silver-mining boom, these gold rushes profoundly affected both the circulation of coinage and the United States Mint’s expansion.

At the start of the 19th century, the nation’s single mint at Philadelphia faced a severe shortage of gold and silver. Yet by the end of the century, the nation was awash in gold and silver and had seen the establishment of six federal branch mints and 20 short-lived private mints. When the Philadelphia Mint began striking coins in 1793, the United States had no domestic gold and silver sources and obtained its limited supply through foreign trade and by melting down the mix of foreign coinage then in circulation.

During the early 1800s, the Philadelphia Mint coined only about 25,000 troy ounces of gold per year. But production took a big jump in 1820 when the mint, thanks to its growing stockpile of gold from new mines in North Carolina, struck 263,800 Capped Head $10 half eagles from 118,712 troy ounces of gold.

Farm-Boy Find Makes History

The nation’s first documented gold discovery was made in 1799, when a farm boy near present-day Charlotte, North Carolina, found a baseball-sized rock that weighed an astounding 17 pounds. That rock served as a doorstop for three years until a goldsmith identified it as gold. The boy’s father, John Reed, then partnered with neighbors in a successful placer-mining venture that triggered the nation’s first gold rush.

But the only buyer willing to pay a fair price for North Carolina gold was the Philadelphia Mint, which was 450 miles and three weeks distant over rough, dangerous trails. Another problem was that high shipping and insurance costs often amounted to ten percent of the gold’s value. Despite these difficulties, North Carolina miners still managed to send their first small gold shipment to the Philadelphia Mint in 1804.

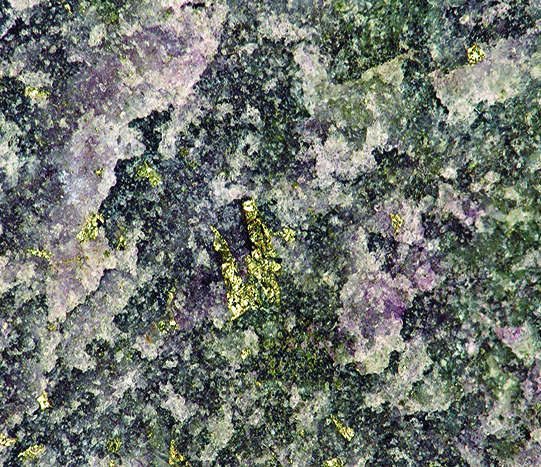

By 1825, John Reed’s mine alone had yielded 5,000 troy ounces of gold worth nearly $100,000—a fortune at the time. And as the easy-to-mine placers depleted, miners turned to underground workings to extract even more gold from quartz veins. By the early 1830s, 10,000 miners and mill workers in 54 North Carolina mines had boosted annual gold production to 35,000 troy ounces. In 1834, the Philadelphia Mint, now sitting on a growing stockpile of bullion, set a record for gold coinage, striking 719,835 Classic Head and Capped Bust $5 half eagles and $2.50 quarter eagles from 344,000 troy ounces of gold.

But few U.S. gold coins ever reached North Carolina, and German emigrant Christopher Bechtler saw that as a business opportunity. In 1831, he opened a private mint at Rutherfordton, west of Charlotte, to strike $5, $2.50, and $1 gold coins. By 1838, Bechtler’s mint had turned out $2.24 million in coinage from 112,000 troy ounces of gold, along with 70,000 troy ounces of bullion worth another $1.4 million. Bechtler paid a fair price for newly mined gold to gain the miners’ confidence, encourage mine production, and provide a widely accepted medium of exchange to boost North Carolina’s developing economy.

Meanwhile, in 1828, prospectors found gold in northern Georgia, setting off another gold rush. Boomtowns like Dahlonega, its name an anglicization of the Cherokee word talonega for “yellow money,” sprang up overnight. The first shipment of Georgia gold—a substantial 25,000 troy ounces—reached the Philadelphia Mint in 1832. In Georgia, gold mining followed the pattern already established in North Carolina: miners worked placers before developing dozens of small underground mines.

In 1830, Templeton Reid had opened a private mint at Dahlonega, which predated North Carolina’s Bechtler Mint by one year as the nation’s first private gold-coin mint. By 1835, the Reid mint had struck $10, $5, and $2.50 coins from 20,000 troy ounces of Georgia gold. Through the combined output of the North Carolina and Georgia mines, the Philadelphia Mint doubled its gold-coin production during the 1830s. But shipping gold from the mines to Philadelphia remained difficult, and few newly minted U.S. gold coins ever made it to the South to stimulate the regional economy.

Mint Act Shapes the Future

Therefore, Congress passed the Mint Act of 1835 to authorize the establishment of three federal branch mints. The new mints at Charlotte, North Carolina, and Dahlonega, Georgia, would strike only gold coinage. The third mint, located in New Orleans, Louisiana—then the largest U.S. port in terms of foreign trade—would strike both gold and silver coinage, mainly from Mexican bullion obtained in trade. Another reason for locating this mint in New Orleans was its proximity to new gold discoveries in central Alabama (which never met expectations).

The three new mints began production in 1838. By 1845, two of these mints, the Charlotte Mint, using a “C” mint mark, and the Dahlonega Mint, using a “D” mint mark, together had struck $12 million in Liberty and Liberty Coronet $5 half eagles and $2.50 quarter eagles from 600,000 troy ounces of gold.

The Carolina and Georgia goldfields’ collective output is poorly documented, but by 1847 it had probably exceeded 1.5 million troy ounces worth roughly $30 million. Although production was declining by then, these mines had made a substantial contribution to the national economy. They contributed to double the amount of circulating gold coinage, brought branch mints to Charlotte and Dahlonega, and established a base of technological gold-mining expertise that would soon find use elsewhere.

In 1848, prospectors discovered fantastically rich placer deposits on the American River in California’s Sacramento Valley. This strike set off a monumental rush that would draw a quarter-million Americans west, including many out-of-work North Carolina and Georgia gold miners.

In 1849, its first full year of mining, California produced 300,000 troy ounces of gold. In 1852, the aptly named “Golden State” turned out four million troy ounces of gold worth $80 million. That year’s production alone amounted to more than three times all the gold that had been mined in North Carolina and Georgia over the past 50 years. In 1848, California’s military governor had shipped 228 troy ounces of newly mined gold to the Philadelphia Mint, where it was coined into 1,389 Liberty Head $2.50 quarter eagles. The reverse of each coin was punched with the letters “CAL” to identify it as the first of what would be many millions of U.S. coins made from California gold.

But getting California gold to the Philadelphia Mint required a dangerous, 10,000-mile-long, “round-the-horn” sea voyage, or two shorter voyages linked by a difficult overland transit of the Central American isthmus.

With California knee-deep in gold dust but with little circulating coinage, 15 private mints began striking gold coins in denominations from fractions of a dollar to twenty dollars. Many produced undersized coins that gained only limited acceptance. The successful California private mints that turned out “full-weight” coinage included Moffat & Co., Kellogg & Co., and Wass, Molitor & Co.

In 1852, Congress authorized the establishment of a branch mint in San Francisco. In 1854, its first year of operation, this new mint with its with its “S” mint mark struck $6.8 million in $20 eagles and $10 half eagles from 300,000 troy ounces of California gold—half as much as the 15-year output of the Charlotte and Dahlonega mints combined.

In 1848, the four eastern U.S. mints—Philadelphia, Charlotte, Dahlonega, and New Orleans—had coined 210,000 troy ounces of gold.

But in 1855, these four mints and the new San Francisco Mint coined 2.25 million troy ounces of gold. And, in 1856, the San Francisco Mint alone struck 1.89 million $20 Liberty double eagles from 3.4 million troy ounces of California gold.