By Joshua McMorrow-Hernandez

For many people, the phrase “treasure hunting” conjures up the fantastic vision of sweeping a metal detector along a sandy shoreline with giddy anticipation of finding valuable booty that once belonged to pirates from days of yore. Yet, for thousands of coin collectors, treasure hunting has a more realistic—though equally adventuresome—connotation.

Hiding inside rolls, within bulk lots, and even right under the noses of coin dealers across the country are troves of die varieties. These include doubled dies, repunched mintmarks, overdates, transitional designs, and myriad other exciting coins just waiting to be discovered.

Die varieties represent one of the most colorful, fascinating avenues in numismatics. Complex—some might say “spicy”—alternatives to traditional date-and-mintmark or type collecting, die varieties have captivated collectors for decades, with some focusing their numismatic careers as variety specialists.

Until the mid-20th century, the study of die varieties was largely relegated to the proverbial back alleys of the hobby. This changed with the detailed research of Dr. William Herbert Sheldon, whose industry-defining book Early American Cents: 1793-1814: An Exercise in Descriptive Classification with Tables of Rarity and Value (Harper & Brothers) hit the collecting scene in 1949 and changed the way hobbyists looked at their coins—and how they graded them. Dr. Sheldon introduced his landmark 1-70 numerical grading scale in that publication.

Sheldon’s book, revised in 1958 and retitled Penny Whimsy, has gone on to numerous reprints as one of the most fundamental printed works in coin collecting. Sheldon’s work and the rest of the variety-collecting realm received a huge boost in interest with the discovery of the 1955 doubled die Lincoln cent, which turned up in circulation just as the coin collecting boom was reaching its zenith. It was serendipitous: The numismatic community became entranced with doubled dies, and error-variety collectors began checking their change with the hopes of finding more of these unusual coins.

Since the 1950s, many other books have joined Sheldon’s to help educate collectors on the evolving, nuanced world of varieties. Among the most popular of these books is Comprehensive Catalog and Encyclopedia of Morgan & Peace Dollars, by Leroy Van Allen and A. George Mallis. Their collaborative effort, which spawned the Comprehensive Catalog and Encyclopedia in 1971, led to the recognition of so-called “VAM” (Van Allen and Mallis) dollars, which are Morgan and Peace silver dollars with various attributed varieties and other die anomalies.

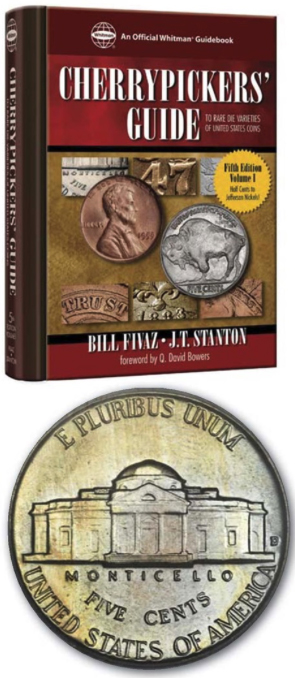

These days, many collectors are being introduced to die varieties through the Cherrypickers’ Guide to Rare Die Varieties of United States Coins, an iconic reference guide co-authored by Bill Fivaz and J.T. Stanton that profiles some of the rarest, most popular die varieties for each of the major United States coin series. With multiple updates by Whitman Publishing since the first edition was released in 1990, Cherrypickers’ Guide is one of those must-have directories for those who are looking for hidden treasures.

Fivaz, who was inspired by his own interest in seeking varieties, has discovered many gems “hiding” virtually in plain sight. “Many years ago, I cherried an 1829 Curled Base 2 Bust dime in Good-Very Good condition and made a handsome profit on it,” he said. The Professional Coin Grading Service (PCGS) estimates there are only 40 of these coins in existence across all grades, and a specimen such as Fivaz’s lists for around $6,250 today.

“At another time, I bought a BU roll of 1944-D Lincoln cents after discovering 17 of the Type I D/S overmintmark coins hiding within.” PCGS estimates there are 5,000 examples, and in MS-63 Red-Brown prices start at around $325 apiece. Indeed, the arena of modern coins has proved a successful hunting ground for Fivaz, who has handled thousands of die varieties.

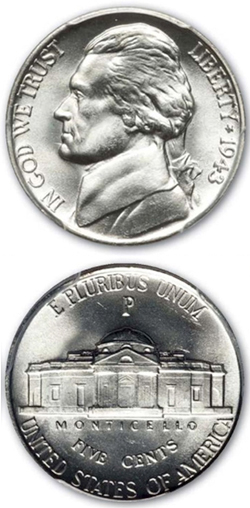

“Another nice roll purchase was a BU roll of 1943-P war nickels that had 21 of the ‘Doubled Eye’ variety among the coins.” With 35,000 estimated to exist, these sell for about $150 each in MS-63; there are just seven survivors in the top grade of MS-67.

“Just recently, I cherried myself, from rolls I had in stock for years, a 1968-D Jefferson nickel with Full Steps (“FS”), which was graded by PCGS as MS-65 FS, and a 1945-S Jefferson nickel with Full Steps, certified by PCGS as MS-65 FS—a real bear to find!” PCGS lists a population of just one for the 1968-D MS-65 FS, with a value of more than $15,000; meanwhile, the 1945-S MS-65 FS is among 63 other similarly graded survivors, trading for a respectable $290.

“These brought insane prices in auctions to collectors who are competing for the highest-quality specimens for their registry sets,” he says. “So, cherrypicking is applicable not just for varieties, but also for ‘common’ late-date coins in superb, rare condition.”

Fivaz, who has collected coins since 1950, helped oversee the creation of The Combined Organization of Numismatic Error Collectors of America (CONECA) in 1983, which was formed as a marriage of the Collectors of Numismatic Errors (CONE) and Numismatic Error Collectors of America (NECA). Today, CONECA (www.conecaonline.org) has become the de facto national error-variety organization and serves as a comprehensive resource for new and seasoned enthusiasts alike.

But, how does Fivaz, a legendary cherrypicker in his own time, do it? The popular author and speaker is always glad to share some of his treasure-hunting secrets. “Become aware of where to look on various series to stand a good chance of spotting doubled dies, misplaced dates, repunched mintmarks, etc. As an example, doubled dies on Washington quarters very often are seen on the motto on the obverse, the eagle’s beak, and claws on the reverse,” he says. “On Seated Liberty coins, misplaced dates gravitate to the denticles below the date and in the rock above the date. Be conversant with these potential ‘ripe’ areas for every series and concentrate first on those when foraging for varieties.”

He also suggests buying reference books for each series. “Most have excellent photos illustrating the location(s) on where to look,” he adds.

One area in which he believes collectors need to become better educated is in differentiating doubled dies from strike (“mechanical” or “machine”) doubling. “There is an excellent section on this in the back of each issue of the Cherrypickers’ Guide.”

And there’s this encouraging insight from Fivaz: “There are many unreported major and semi-major varieties out there, so don’t be locked into just those that have already been reported. New ones are being discovered all the time, so get your name attached to one.”

Kevin Flynn got his start in coin collecting as a Boy Scout, chasing after a merit badge in coins. He picked up the hobby again as an adult in 1989, and the self-declared “underdog” discovered a passion for two-cent coins, a series he calls “an underdog”. However, unlike two-cent coins, Flynn’s existence is not one of relative obscurity. The prolific writer has penned more than 50 books, including many in his Treasure Hunting series, which focuses on finding die varieties and other peculiar coins among various United States series. But don’t call his pursuit of error varieties “cherrypicking”. He much rather prefers the term “treasure hunting”.

“That’s what it is,” he says.

Flynn is passionate about searching for die varieties, errors, and other oddities.—not necessarily because of the monetary profit he might earn in selling an overlooked doubled die or overdate bought from a dealer’s table, but because examining unusual coins can help a collector discover so much about the history of a coin, how it was minted, the die-making processes, and more.

“How did the doubled die happen?” he wants to know. Flynn, a passionate numismatist who spends much of his recreational researching at the National Archives offices in Washington, D.C., and Philadelphia, wants to know the “whys” and “hows” behind every variety he finds.

And how does he find varieties, errors, and other coins worth writing about? “You’ve got to search the right environment,” he says. “It’s hard at big coin shows. You’ve got people there who are like vacuums, who go from table to table sucking up overdates, repunched mintmarks, and other varieties.” Small shows are better hunting grounds for many folks, according to Flynn. But big show or small, he says, the early bird catches the worm. “I like going to the Florida United Numismatists shows because they offer the Early Bird pass, which means I can go in and get a look around before others do.”

Regardless of the size of the show, certain dealers already know what they have, making it difficult to find underpriced varieties at their tables. “If you go to a dealer who has all of his VAM dollars neatly marked, he’s already checked out his coins and has looked for the varieties.” Besides, Flynn says, it’s tough to find any good deals in commonly pursued series such as Buffalo nickels or Morgan dollars, both of which are known for their high-priced varieties. “Everyone’s looking for the Top 100 VAM dollars. You’ve got to check out the obscure series, the ones that practically nobody else would think of when looking for errors, such as two-cent coins, three-cent silvers, and three-cent nickels.”

Collectors should exercise some etiquette when looking for diamonds in the rough. “You don’t want to walk up to a dealer and spend 15 minutes poring over his coins with a copy of a die variety book in your hands. This will upset the dealer, who will think he has coins he’s selling for way less than they’re worth.” Flynn says the best situations are those in which one can look through an album of coins at a more leisurely pace.

“You really should focus on one or two series and know in your head what you’re looking for and where on the coin you should be looking for it,” he suggests. “Have a list in your head—but don’t stop with die varieties.”

“There are,” he reminds treasure hunters, “many matte proof Lincoln cents and Buffalo nickels slabbed as business-strike coins.” Unlikely, yes—but not at all impossible. “You know how many people spent the proof nickels they bought at eight cents apiece in the 1910s to buy a loaf of bread during the Great Depression?”

Matte proofs can be picked out from business strikes by those who know what diagnostics to look for. “Die markers are the key to distinguishing matte proofs from MS specimens.” He adds, “and this is an area that many simply overlook.”

When people begin collecting coins, they often turn to Lincoln cents. They’re cheap. They’re fun. They’re plentiful. And they’re easily available by the thousands to virtually anybody who wants them. A box of 2,500 can be bought from any bank for just $25. In those boxes are 50 rolls, and in each of those 50 rolls are 50 one-cent coins ripe for the cherrypicking. They’re the type of hunting grounds people such as Charles Daughtrey love to search.

He wrote Looking Through Lincoln Cents: Chronology of a Series (Zyrus Press, 2004), a book that explores numerous doubled dies, repunched mintmarks, overdates, and other scintillating varieties. Daughtrey’s research stretches back to his childhood, when his father got him involved in coin collecting. He dove into varieties in 1988, when he was stationed in Germany, serving in the United States military. “I subscribed to numismatic magazines and found John Wexler’s The Lincoln Cent Doubled Die for sale and bought it. The rest, like they say, is history.”

Daughtrey says one of his best finds came in May 2005 at the Central States Numismatic Society convention in St. Louis, where he bought an About Uncirculated 1911-D/S Lincoln cent for $60, then the price of a “regular” AU 1911-D cent. “After I bought the coin, I went outside to make a phone call to a private collector and sold the coin for $2,400.” He used the money to purchase more rolls of coins to search through.

Daughtrey says uncirculated rolls are his prime territory for finding many varieties at once. “That’s because the Mint packages coins in bags that all came from the same run on the presses, so duplication of coins struck by a particular die is common. In one example, I opened a 1960-D rolls of cents and 48 out of 50 were die varieties, yet there were only five different dies represented.” He adds, “when searching dealer stock or pocket change, this would never occur.”

He says collectors can be aided in their error-variety pursuits with a decent 10x-power loupe and good lighting. “Of course, if you plan to hunt for varieties regularly, like I do, I would recommend a good stereo-optical microscope. I always advise collectors to spend good money on their optics because we get only one pair of eyes.”

Then there’s experience, something that every good cherrypicker eventually snags with enough time. “Using books and websites will help you understand what it is you seek,” Daughtrey says, “but much like bank tellers training to handle money, the more normal and real stuff you handle, the more likely you will recognize something odd when you see it.”

Ultimately, patience pays off. “Cherrypicking coins is indeed a treasure hunt,” he says. “I compare the feeling to the times I have been gold prospecting and actually managed to find colors in the pan. It really doesn’t matter that there is a market value for what I have found, the accomplishment is there regardless of market value,” he adds. “It’s hope, anticipation, surprise, and accomplishment—in that order. Then it all starts over again for the next good find.”

But those finds don’t necessarily come frequently. “Impatient people will find [cherrypicking] a very boring activity, because finding the little gems does not happen very often. In typical circulated cents, it can take more than a thousand coins to find one decent die variety worth keeping.” Sometimes, tired—or impatient—eyes can deceive anyone. “Just remember that when you go through a couple hundred pennies and think you’ve found a dozen varieties. They wouldn’t be called ‘rare’ if people found them often.”

John Wexler is a busy man. His website, Wexler’s Die Varieties (http://doubleddie.com), comprehensively lists thousands of error-varieties, and more are constantly being added as collectors send in their unusual-looking coins for potential attribution of newly discovered die varieties. “I average two to three packages (five coins per package) per postal-service business day,” says Wexler. “There is a good core of die variety enthusiasts out there who really know what they are doing and there are a lot of newbies just learning,” he adds.

Not all of those coins he receives are real die varieties or errors. “I’d have to put it at a 50-50 split.” For Wexler, the variety attribution process begins with determining whether a coin comes from a type of die with peculiarities, such as a doubled die or repunched mintmark, or bears one of the more common forms of mishaps, such as mechanical doubling or die deterioration, which are frequently confused with doubled dies—the subject at the root of many inquires he receives from collectors.

When a submitted coin checks out as a genuine variety, he has to confirm whether the coin is already attributed as a variety or is a new one. “If it is a new listing, a variety number will be assigned to the variety, an adequate write-up with the variety diagnostics is completed, and photos of the doubling and die markers are taken,” Wexler explains. “The new listings are then posted periodically on my own website and are not shared with others, unless there is a specific request.”

Like searching for die varieties is a passion for countless collectors, helping these collectors attribute their coins is a labor of love for Wexler. He began collecting coins at the age of 7. “My interest in die varieties developed several years later.”

He owes his love of die varieties to one of his coin-collecting uncles. “During family visits, he would bring a large jar of Lincoln wheat cents and give them to me to look through for dates that I needed. Eventually, there was just a single ‘hole’ remaining in the folder that contained the Lincoln cents from 1941 through 1958,” he recalls. “The 1955-S remained quite elusive until my uncle showed up for one of his family visits without the large jar I was accustomed to searching through. Instead, he handed me just one Lincoln cent—a nice, shiny 1955-S. The folder was complete.”

The young Wexler couldn’t believe his search was over, and he kept opening his filled folder to admire his newly completed collection. “During one of those admiration sessions, I noticed something peculiar. There was a blob of metal between the ‘B’ and ‘E’ of ‘LIBERTY’ that resembled another letter. I started searching all of my Lincoln cents more closely and found other types of die chip errors,” he recalls.

“After some time had gone by, I found a book by Frank Spadone that was titled Major Variety and Oddity Guide of United States Coins. It was refreshing to find out that I was not the only one finding odd coins,” he says. “Fast-forward to 1971, when my search for ‘BIE’ errors and clogged letters in ‘LIBERTY’ led me to the discovery of a 1971 Lincoln cent with a strong obverse doubled die. The following year saw the release of the major 1972 Lincoln cent obverse doubled die, along with several ‘lesser’ varieties. I was hooked.”

Of course, Wexler wasn’t the only collector excited about the 1972 doubled die cent. As evidenced by the public frenzy that accompanied the discovery of the 1955 doubled die cent years later and the media sensation over the 1995 doubled die cent over two decades later, Wexler confirms doubled dies are the most popular of all die varieties, with the most popular varieties, such as the aforementioned 1955, 1972 and 1995 doubled die Lincoln cents, often earning their own pre-labeled portals in major coin albums.

Asked about the health of the die variety market in the wake of the Great Recession of 2007-09, Wexler rhetorically asks, “There has been a ‘Great Recession’ in the coin industry? I believe that the die variety segment of the hobby has weathered the storm quite well.” He says doubled dies have done a particularly good job in maintaining their market vitality. “This is due mostly to the publicity this die variety type receives.”

Back when coins like the 1972 doubled die, and even the 1995 doubled die, hit the scene, publicity was largely driven by magazine and newspaper articles, radio interviews, and television news broadcasts. The situation, of course, has changed significantly since the dawn of the 21st century with the advent of social media, and this has helped bring in more collectors seeking the kinds of coins Wexler and his error-variety colleagues specialize in.

“I can’t even begin to quantify the number of die variety collectors, but I can say that the numbers are growing faster than I have ever seen them grow before,” he says. “Part of the reason for this influx of die variety collectors is social media. There are Facebook pages, blogs, and YouTube videos all devoted to die varieties and die variety collecting.”

News of variety finds shared on social media has helped inspired many people to jump into collecting die varieties or begin looking for them in rolls and pocket change. “There are still plenty of nice die varieties out there waiting to be found,” Wexler assures. “Just ask Megan Greene if you don’t believe me—she is a stay-at-home mom who searched rolls of Lincoln cents obtained from a local bank and hit the die-variety jackpot when she found a 1969-S Lincoln cent with a major obverse doubled die that’s worth five figures.”

Wexler has one, simple piece of advice for collectors who hope to hit pay dirt while digging up similar error-variety treasures of their own: “Keep looking!”

Want to receive COINage magazine in your mailbox or inbox? Subscribe today!

I Have a 1969-S Mint

I Have A 1951 S

San Francisco

One Cent

Wheat Penny