Many numismatists enjoy the Old West romance of the Carson City and Denver Mints, the Gold Rush fervor that inspired the San Francisco Mint, and the mystique of the New Orleans Mint. The mist of Civil War lore surrounds the Charlotte and Dahlonega Mints, and the West Point Mint piques the curiosity of those who embrace modern coins. Then there is the story that often goes untold – the one that started it all for American numismatics as we know it today. It is the story of the Philadelphia Mint – the “mother mint,” as some like to say.

The United States Mint was established by the Coinage Act of 1792, also known as “The Mint Act” and officially titled An Act Establishing a Mint, and Regulating the Coins of the United States. When this legislation was enacted by the second United States Congress and signed into law by President George Washington on April 2, 1792, it was decided that the place where the nation’s first mint would be located was Philadelphia, which, at the time, was serving as the temporary capital of the United States.

The Legacy of the Philadelphia Mint

The legacy of the Philadelphia Mint spans four sites and more than 225 years. Some may say it’s a scrappy tale, encompassing a motley crew of colorful characters – even a menagerie of animals, including horses and oxen. What else would you expect from the City of Brotherly Love, whose loveable icons include inventor Benjamin Franklin, fictional prizefighter Rocky Balboa, the cracked Liberty Bell, and distinctive culinary concoctions that include cheesesteaks and tomato pie?

It’s a story of survival and evolution that took the Philadelphia Mint from its humble beginnings situated in a cramped huddle of small buildings on a tiny lot to becoming the largest government mint in the world.

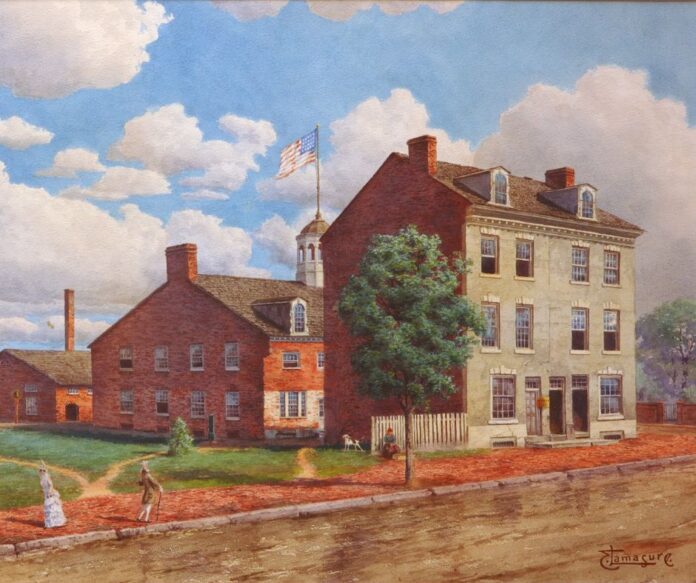

Building the First Philadelphia Mint

Passage of the Coinage Act of 1792 swiftly led to the raising of the United States Mint, the first federal building constructed under the U.S. Constitution. This first mint, consisting of three structures, went up near the intersection of Seventh and Arch Streets in Philadelphia. It was lean times for the fledgling United States. The U.S. Constitution had been written just five years earlier, in 1787, was not ratified until 1788, and had only begun operating in 1789, the year the first federal Congress of the United States convened.

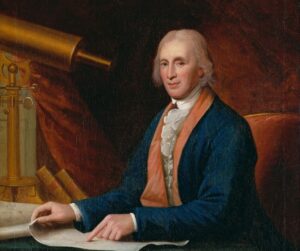

David Rittenhouse & His Role

David Rittenhouse was exactly the sort of man President George Washington sought to lead as the founding director of the United States Mint – especially considering that Great Britain tapped Sir Isaac Newton himself to lead the Royal Mint a century earlier. Rittenhouse was a scientist’s scientist, a man who understood Isaac Newton’s laws of motion and gravity, a maker of fine clocks and mechanical models of the solar system. He would best be described as an astronomer and mathematician. He formally accepted the position on July 1, 1792, though he had already begun assisting the United States government in finding just the right site in Philadelphia for the new mint.

“I feel that David Rittenhouse’s role has been long misunderstood,” remarked numismatic historian and From Mine to Mint (Seneca Mill Press) author Roger Burdette. “He was the manager, handled the records, and reported to Congress and the President. But he had no practical coining knowledge. Additionally, he was left out of almost all correspondence relating to contract coinage and Matthew Boulton’s equipment,” the latter a reference to a British industrialist who utilized efficient steam-powered presses that were faster than the screw-press equipment of the day. “Rittenhouse was too infirm to travel to England and his only involvement was a need to import copper sheets, which was handled by Thomas Pinckney.”

A “Contraption” Created by Voigt

Burdette noted the early U.S. Mint, built near the intersection of Filbert and Seventh Streets in Philadelphia, was a “contraption” created by Henry Voigt, the chief coiner of the United States Mint who had drawn on his experiences in mint work in his native Germany. “Equipment depended on mechanical skills of several local machinists including Adam Eckfeldt, who had built a press for John Harper before the mint was authorized,” explained Burdette.

Machinery was powered by the brute strength of man and beast – horses and oxen. “The technology was crude and obsolete. As Ambassador Thomas Pinckney noted in a 1792 letter to Boulton, ‘…the coinage being at present intended on a limited scale, the usual instruments of coinage will be made use of [in] the present establishment not requiring the more expensive improvements of the steam engine.’” After initial strikings of silver half dismes and other pieces, the Philadelphia Mint was mass producing copper coins in 1793, with the Chain AMERI large cent the first of these coins to his large-scale circulation.

Rough Going at the Early Mint

There was no comparing the ramshackle infant United States Mint to any of the established mints in Europe. “The same basic technology was in use, but European equipment quality and coining knowledge were far beyond anything available in the United States – or anywhere in North America.”

By the turn of the 19th century, the mint was at a crossroads. Would it relocate to Washington, D.C., where other federal government offices were moving as the District of Columbia became the nation’s permanent capital? Or would the financially strapped mint, with its revolving door at the administrative level and incapability of producing ample coinage for the young nation, even continue at all?

Burdette believed that had the mint moved to Washington in 1800 or 1801, one of the biggest differences would have been the use of water-driven equipment instead of horsepower. “A central argument for leaving the mint where it was included proximity to banks and other bullion sources and good access to Philadelphia’s port for shipment of copper from England,” Burdette remarked.

“The greatest difference would have occurred if the United States had actively followed up on installing one of Boulton’s steam-powered presses and rolling mill.” But that wasn’t to be… Steam power wouldn’t be adopted by the United States Mint until the mid-1830s, by which time the nation’s coining operations had moved into a much statelier facility in Philadelphia.

Full Steam Ahead

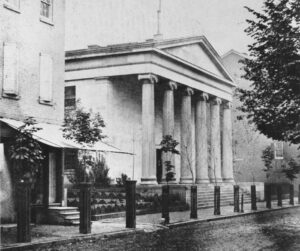

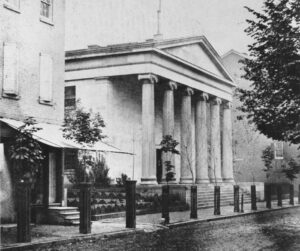

The second Philadelphia Mint opened in 1833 at the corner of Chestnut and Juniper Streets. Designed by renowned architect and civil engineer William Strickland, the second Philadelphia Mint was much larger than its predecessor and bore white marble and Grecian-inspired columns. In addition to enjoying the bigger digs, the U.S. Mint was on the verge of a revolution that would vastly improve its coining capacities.

“In 1833 Franklin Peale, a skilled mechanic employed at the Philadelphia Mint, was sent to Europe to study the latest techniques in coinage, especially the presses,” said numismatic researcher and historian R.W. Julian. “Prior to his return in the late spring of 1835, it had been decided to furnish the new branch mints [to begin operations in 1838 in New Orleans, Dahlonega, and Charlotte] with screw presses – the kind used at the Philadelphia Mint since 1792.”

Modern Steam Coinage Presses

During his time in Europe, Peale visited the Paris Mint, which boasted modern steam coinage presses – technology he believed the U.S. Mint should adopt. An inspired Peale sketched drawings of a steam press he could devise for the U.S. Mint based on the steam technology he saw at the Paris Mint and incorporating his own modifications. “Upon his return to Philadelphia, Peale persuaded the new mint director, Dr. Robert M. Patterson, that the idea of a screw press should be dropped in favor of a steam coinage press. Arrangements were made to have a stream coinage press constructed in Philadelphia, using the drawings made in Paris but with improvements devised by Peale.”

Peale’s new steam-operated presses began service at the Philadelphia Mint on March 23, 1836. “[It] proved a resounding success,” Julian remarked. A screw press required as many as five operators and could produce 14,000 coins on a good day, whereas the steam press needed just one operator and could church out 40,000 or more per day. “With this in mind Director Patterson changed the orders for the branch mints; screw presses were out, steam coinage presses in.”

Leaping into the Future

“The introduction of the steam press was a giant leap forward for the mint,” explained numismatic researcher Len Augsburger, executive director of the Newman Numismatic Portal and coauthor of The Secret History of the First U.S. Mint (Whitman Publishing). The physical scale of the second mint would soon be outsized by ballooning coin production runs and the need for more minting equipment.

The once-proud “Grecian Temple,” as some called the 1830s-vintage mint building, was showing its age in the waning years of the 19th century. “By the early 1890s, the second mint was old and decrepit,” remarked Augsburger. “Senator Thomas H. Carter, who advocated for the [third] building, personally visited the second mint and described ‘cold, dark, subterranean’ conditions not fit for human labor.” The legislation for the new Philadelphia Mint was passed in 1891. “The third facility again increased the capacity of the mint, moving to a full city block.”

Beaux-Arts Building

Opening June 13, 1901, the massive $3 million Beaux-Arts building designed by William Aiken opened its doors as a modern, state-of-the-art mint. Designed for efficiency and fully electric powered, the new mint boasted wide, sun-splashed rooms, dedicated areas for various stages of the minting process, and grand accommodations for visitors. A focal point of the mint was a rotunda housing the mint’s massive coin collection, on exhibit for public viewing.

Expansions and improvements over the next several decades kept the third Philadelphia Mint agile as minting needs expanded and contracted. By the swinging ‘60s, coining operations at 1700 Spring Garden Street had outgrown their quarters and it was time once more for the United States Mint to plan for a new, larger facility.

Arch & Fith Streets

On September 17, 1965, Mint Director Eva B. Adams oversaw a groundbreaking facility for the fourth Philadelphia Mint at Arch and Fifth Streets – just a few blocks from the location of the first United States Mint. The modern $37 million building, a monstrous study in the Brutalist architectural movement en vogue during the Space Age, was dedicated on August 14, 1969. Minting moved across Center City Philadelphia and the 1700 Spring Garden Street location was converted into the Community College of Philadelphia.

Meanwhile, the Philadelphia Mint building at Fifth and Arch and on the northeastern fringes of Philadelphia’s tourist-jammed Independence Mall continues striking away nearly two million coins per hour each business day. The outstanding efficiency and output of the Philadelphia Mint ensures the sufficiency of the facility even a half century after striking its first coin. “Given the rise in electronic payments, not to mention the proliferation of change jars in retail establishments, it’s clear that the public has less and less use for circulating coinage,” noted Augsburger. “It seems unlikely that we will need a fifth Philadelphia Mint anytime soon.”

This article about Philidelphia mints previously appeared in COINage magazine. To subscribe click here. Article by Joshua McMorrow-Hernandez.