Coin mintages are an official report on how many strikes of a specific issue were produced. They are one of the key statistics about any coin and are readily available for most United States Mint coins. New collectors and seasoned numismatists often refer to mintage figures to help ascertain how rare or common a coin is.

Many leading price guides publish coin mintages for each issue listed when this data is available. The U.S. Mint provides this information in its annual Mint director reports and it’s provided to the public by the government not only for the sake of transparency in public accounting but also for the benefit of numismatic knowledge.

WHY COIN MINTAGES DON’T ALWAYS TELL THE WHOLE STORY

Coin mintages give coin collectors some basic background about a coin’s rarity. It’s certainly logical on a surface level to deduce that low-mintage coins are rarer than higher-mintage coins. But digging a little deeper, numismatists will see that there’s more to know about coin rarity than just going off mintage figures alone.

This is demonstrated by simply looking at one of the most famous coins in the world: the 1933 Saint-Gaudens double eagle. This coin has been making headlines since its striking more than 90 years ago.

1933 Double Eagle

The 1933 double eagle was among the last of the gold coinage struck for U.S. circulation before President Franklin Delano Roosevelt issued Executive Order 6102. This Great Depression-era law forbade “the hoarding of gold coin, gold bullion, and gold certificates within the United States.”

The order, enacted under the authority of the Trading with the Enemy Act of 1917 as amended by the Emergency Banking Act of 1933, limited private ownership of most gold in excess of $100. Contrary to popular belief, gold ownership was not completely banned. There were exceptions for rare coins and gold used in certain industries, such as dentistry and artistic purposes.

The order compelled Americans to deposit their gold in the interest of ending a banking crisis while providing the government with the necessary bullion holdings to print more money during a period when the nation was still on the gold standard. This helped spur the economic revival of the nation’s hampered economy, particularly as millions were put to work through Roosevelt’s New Deal programs. But it also brought an end to circulating gold coinage, which was no longer declared legal tender by the Gold Reserve Act, which Congress passed in 1934.

WINDING DOWN GOLD COINAGE PRODUCTION

In the wake of Executive Order 6102, which required Americans to deliver their gold by May 1, 1933, the U.S. Mint began winding down production of gold coinage, which was later melted. Among the coins ordered for melting was the 1933 double eagle, which saw a total mintage of 445,500. Nearly all were supposed to have been destroyed, with two being spared for inclusion in the United States National Numismatic Collection.

However, several of the coins were stolen (with suspicion that the U.S. Mint cashier was involved), with one purchased by King Farouk of Egypt in 1944. The Farouk specimen disappeared for more than 40 years after the Egyptian king was overthrown in 1952. But the U.S. Secret Service seized the coin when it turned up in the hands of British coin dealer Stephen Fenton in 1996. The matter was settled in court, with the U.S. Treasury legally issuing and monetizing that single specimen, which was sold in 2002 at public auction for $7,590,020 to become what was then the world’s most valuable coin ever sold in public auction. The incredible auction performance of the 1933 Saint-Gaudens double eagle drew about a dozen other authentic specimens out of the woodwork, though all of those specimens have since been confiscated by the government.

“It’s certainly logical on a surface level to deduce that low-mintage coins are rarer than higher-mintage coins. But digging a little deeper, numismatists will see that there’s more to know about coin rarity than just going off mintage figures alone.”

Meanwhile, the 1933 “Saint” goes on as the world’s most valuable coin. The Farouk specimen further secured its position as the priciest coin when it crossed the auction block again in 2021, that time hammering for $18,872,250.

THINKING BEYOND COIN MINTAGES

Though the example of the 1933 Saint-Gaudens double eagle is certainly one of the most fantastical in all of numismatics, the moral of the story is that relying on official coin mintages alone doesn’t always tell you how common or rare a coin is. As seen with the famous “Saint,” official mass meltings of coins by the government aren’t necessarily reflected in published mintage figures. This is certainly the case with coins that have seen huge numbers meet the hot pots of private smelters.

On this basis, it’s safe to say that virtually all “common” pre-1933 classic gold coins and pre-1965 90% silver coinage exist today in much smaller numbers than coin mintages suggest because of untold numbers of private melts. Many of these coins, often boasting mintage figures well into the millions, were melted during periods of high bullion prices. Periods of mass meltings were seen during the precious metals boom of the late 1970s and early 1980s, runs of high gold and silver prices around 2011-12, and coinciding with the height of the COVID pandemic in the early 2020s.

COURTESY HERITAGE AUCTIONS, WWW.HA.COM.

NET NUMBER OF SURVIVORS

There’s some degree of guesswork involved when accounting for the net number of survivors for any given gold or silver coin. While the unit volume of government meltings is often enumerated down to the last coin, there’s no telling how many are melted down by private bullion smelters. This means that many issues widely regarded as “common” may be far rarer than what mintage figures reveal.

And it goes beyond silver and gold coins. Copper coins are notorious for their propensity to corrode, with many decimated beyond collectability. This is particularly problematic with early copper coinage, with many issues yielding but a tiny fraction of collectible pieces from the much larger original coin mintages. Between injurious environmental factors and the heavy circulation many early copper coins experienced, a great many half-cent and large-cent issues that numismatists deem “common” are far scarcer than mintages may suggest. Nickel coinage is much more resistant to corrosion than copper. However, these pieces, which in the U.S. are typically made from alloys containing a large percentage of copper, also see notable attrition rates through eventual wear, damage and loss.

The bottom line? Coin mintages provide the collector with a reliable “base” figure on how many of a certain coin were struck. But they do not provide a “hard” figure on how many examples survive, let alone remain collectible.

SURVIVAL ESTIMATIONS VS. POPULATION FIGURES

Where does the collector turn for more pertinent data on a coin’s rarity? That’s where survival estimations and population figures come into play. Survival estimations for any given coin are generally derived from a combination of the frequency of marketplace appearances, rough figures based on how many known collections contain examples of the coin, and knowledge of circulation patterns and expected attrition.

Survival estimates from numismatic experts are based on much research, but they can’t necessarily peg down exactly how many examples of a given issue exist today.

COURTESY HERITAGE AUCTIONS, WWW.HA.COM.

POPULATION FIGURES

Meanwhile, population figures are based on actual census tallies of how many examples of a given coin have been accounted for. Today, population data is typically promulgated by the major third-party grading services, which handle millions of coins a year. But population figures can also be tabulated by simple counts of known specimens, regardless of whether the coins are encapsulated or “raw” unholdered.

While populations provide numismatists with “hard” numbers, they, too, have their shortfalls. For one, populations count only the examples that can be accounted for. They don’t include specimens suspected but unproven to exist. They can also be misleading if used without considering these data in a broader context.

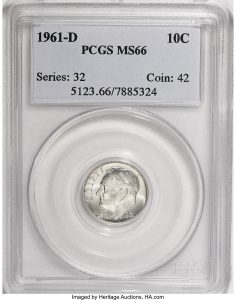

How so? Take the 1961-D Roosevelt dime. This coin has a population of 756 specimens (as of November 2023) graded MS-66 by Professional Coin Grading Service versus a population of three examples in About Uncirculated 50. A person who does not know numismatics might look at those numbers and justifiably assume that AU-50 examples are far rarer than those in MS-66. After all, just three specimens were encapsulated in the lower circulated grade while more than 200 times that figure earned the loftier Mint State grade.

Of course, most collectors who know how third-party grading works will understand that grading fees far surpass the value of a typical circulated 1961-D Roosevelt dime, thus why far fewer are submitted (and encapsulated) in lower grades. But this case exemplifies the pitfalls of considering only population figures in a vacuum – they tell a story, but not the whole story.

CONDITIONAL RARITY & RELATIVE RARITY

This conversation on mintages and rarity would not be complete without an examination of conditional rarity and relative rarity. We know that mintages, survival estimations, and population figures all can be used together to help us better understand which coins are rare and which aren’t. But we also know that some coins are rarer in high grades – some extremely so – than might be assumed by their mintages.

It may not require much understanding of the hobby to expect that older coins are usually harder to find in better grades than in circulated grades. But this line of logic also has its exceptions.

COURTESY HERITAGE AUCTIONS, WWW.HA.COM.

LOW-BALL COINS

Ask any collector of low-ball coins – those in the lowest tiers of the grading spectrum – which coins are toughest to find in worn condition, and they will likely point to classic commemorative coins. These special releases were intended for collectors, and the vast majority were saved in collections, hope chests and other safe places. Thus, relatively few entered circulation, and subsequently many issues are conditionally rare with only honest wear and grading Poor-1, Fair-2 or About Good-3.

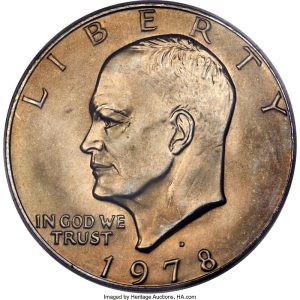

Looking at more recent examples of conditional rarity, one might consider the lack of high-end Eisenhower dollars. Circulation strikes of these large, heavy clad coins were deposited into bags and were frequently marred in transportation from the mint to Federal Reserve locations. Resulting nicks, dings and other imperfections are what usually keep most Ike dollars from grading much beyond Mint State-64. Many of the high-mintage clad business strikes are genuinely scarce in Mint State-65 and downright rare in Mint State-66 or higher.

“As seen with the famous “Saint,” official mass meltings of coins by the government aren’t necessarily reflected in published mintage figures. This is certainly the case with coins that have seen huge numbers meet the hot pots of private smelters.”

Strike designations can also enhance a coin’s rarity, with Full Steps Jefferson nickels, Full Bands Mercury and Roosevelt dimes, Full Head Standing Liberty quarters, and Full Bell Lines Franklin halves categorically scarcer than series counterparts lacking those details.

COURTESY HERITAGE AUCTIONS, WWW.HA.COM.

DON’T FIXATE ON COIN MINTAGES

Collectors need to know the full story of a coin’s background. Coin mintages that are low might call out rarities, but higher production coin mintages don’t always a common coin make either.

The astute numismatist knows coin mintages are just one piece of the puzzle. This is why collectors should always do their research, especially when embarking on a new series or contemplating an expensive purchase.

As the old numismatic saying goes, “Buy the book before the coin!”

This story about coin mintages by Joshua McMorrow-Hernandez was originally published in COINage magazine. Click here to subscribe.