By Steve Voynick

Editor’s Note: This is the conclusion of a two-part series. Enjoy part I >>>

Gold Boom Sparks Mint Expansion

By 1857, California’s mines had yielded more than 20 million troy ounces of gold worth $500 million. Facing huge production demands and short on space, the San Francisco Mint moved to a larger facility in 1874.

Georgia prospectors returning home from California in 1858 discovered placer gold near present-day Denver, Colorado, and started the Pikes Peak gold rush. Three private mints soon opened: Clark, Gruber & Co. in 1860 and two smaller, short-lived operations—John Parsons & Co. and J. J. Conway & Co. —in 1861. Clark, Gruber & Co. would strike $1 million in gold coinage each year for the next three years, with its coins meeting or exceeding U.S. Mint standards.

Also, in 1861, Congress authorized the establishment of a branch mint in Denver. The following year, it approved the Clark, Gruber & Co. building and equipment purchase, not to strike coinage but as a federal assay office to assay and refine gold. It would take another major gold strike 40 years later before Colorado would have a coinage mint.

In 1864, concerned with the proliferation of private mints and competition from first-class operations like Clark, Gruber & Co., Congress finally banned private mints. Production at Colorado’s placer mines peaked in 1862 with 225,000 troy ounces of gold. But while Colorado never lived up to its billing as “the next California,” it did contribute 1.5 million troy ounces to the mint’s growing stockpile of domestically mined gold. By then, the precarious balance of gold and silver upon which the nation’s bimetallic monetary system depended had been thoroughly disrupted. And events already underway in Nevada would disrupt it even further.

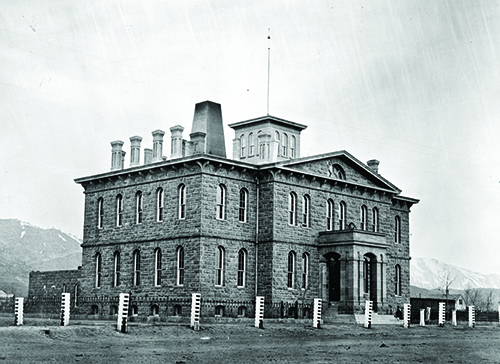

In 1859, Nevada prospectors discovered the Comstock Lode, an enormous silver-gold deposit near Virginia City. The Comstock ore was the nation’s first major source of silver, grading 60-40 in silver-gold value. In its first four years, the Comstock yielded one million troy ounces of gold and a remarkable 30 million troy ounces of silver. Faced with a risky, 250-mile journey to deliver gold and silver to the San Francisco Mint, Comstock mine owners successfully petitioned Congress in 1863 to authorize a federal branch mint at nearby Carson City.

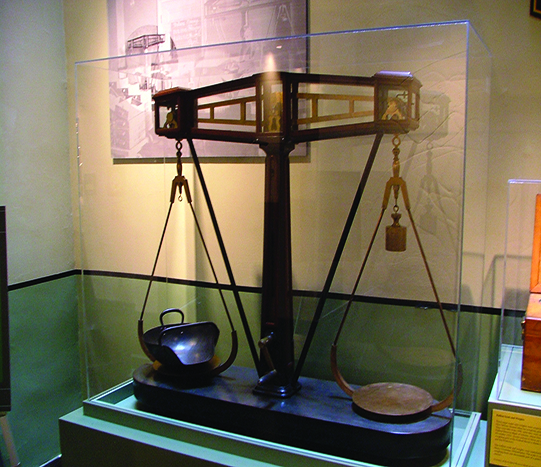

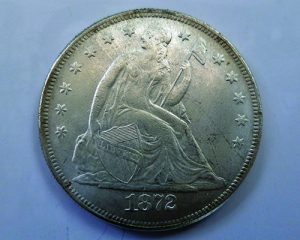

Using a “CC” mint mark, the Carson City Mint opened in 1870 by striking Liberty Seated silver dollars. That year, it coined 12,000 troy ounces of gold and 40,000 troy ounces of silver. The Carson City Mint had a banner year in 1878, striking 2.2 million newly introduced Morgan silver dollars from 2.3 million troy ounces of Comstock silver.

But not all authorized gold-rush mints made it into production. In 1860, discoveries in Idaho, Oregon, and Washington had attracted 80,000 gold miners. This time, getting gold to the nearest mint meant a 900-mile-long journey, first by riverboat down the Columbia River, then south by coastal steamer to San Francisco. To eliminate this shipping problem and boost the amount of circulating coinage in the Pacific Northwest, Congress approved a mint at Dalles City (now The Dalles), Oregon. But construction was half-completed in 1869 when the regional placers, which had yielded about one million troy ounces of gold, were depleted and the mint project was canceled.

Colorado Gold Ore Ushers in New Mint

In 1890, prospectors discovered exceedingly rich gold ore at Cripple Creek, Colorado. In 1900, the Cripple Creek mining district hit its peak with 475 underground mines turning out nearly one million troy ounces of gold. By 1910, the district’s cumulative output had exceeded 17 million troy ounces. Colorado already had a federal assay office from the days of the Pikes Peak gold rush. But when Cripple Creek’s potential became apparent in 1895, Congress approved a branch mint at Denver. Completed in 1904, the Denver Mint opened in February 1906 as the second U.S. branch mint to use the “D” mint mark

In its first year, the Denver Mint struck $20 Liberty double eagles and $10 eagles, and $5 Liberty Coronet quarter eagles from 2.5 million troy ounces of gold, along with Barber half dollars, quarters, and dimes from 3.1 million troy ounces of silver. In 1921, when Morgan silver-dollar production resumed after a 15-year hiatus, the Denver Mint struck 20.3 million silver dollars from 19 million troy ounces of silver.

Today, the San Francisco and Denver mints continue to strike circulating coinage. But the other gold-rush-era mints have faded into history.

At the onset of the Civil War in January 1861, the Confederacy seized the Charlotte and Dahlonega mints and continued limited coin production until the bullion ran out. Following the war, the Charlotte mint was converted to a federal assay office that operated until 1913. The Dahlonega Mint never reopened.

The state of Louisiana seized the New Orleans Mint in January 1861, shortly before joining the Confederacy. Nevertheless, the mint continued operating for several months to strike 2.5 million 1861-O silver Liberty Seated half dollars. Shortly before it closed that April, the Confederacy changed the Liberty Seated half-dollar reverse dies to its design and struck an unknown number of Confederate States of America coins, only four of which are known to exist today. Union forces recaptured the New Orleans Mint weeks later. The mint was reopened in1879 after the end of Reconstruction and struck coinage until closing in 1909.

The Carson City Mint in Nevada produced coinage from 1870 until 1885, then again from 1889 until 1893. From 1879 on, this mint struck gold eagles and half eagles, but only one silver coin—the Morgan silver dollar—produced 14 million. After the 1893 repeal of the Sherman Silver Purchase Act, the Treasury was no longer required to purchase huge amounts of newly mined silver to subsidize the West’s mining industry. The price of silver crashed and the Comstock, along with hundreds of other silver mines, closed. So, too, did the Carson City Mint, which was converted to a federal assay office that operated until 1933.

While the 19th century gold rushes dramatically increased circulating coinage and greatly expanded the U.S. Mint’s capacity, the amount of gold produced during the rushes was not great by modern standards. The combined 10-year output of all the rushes did not exceed 40 million troy ounces of gold. Even the great California rush produced only 4 million troy ounces of gold per year at its peak.

Today, Nevada’s modern open-pit mines alone produce far more gold each year, and have for each of the past 30 consecutive years!

Nevertheless, the 19th century gold rushes left behind a wealth of collectible coinage, a succession of branch mints, and an exciting story of how gold went from the mines to the mints.