By. R.W. Julian

Although numismatics was a lively hobby by the mid-1860s, there was little in the way of a national push towards increasing the number of people involved. Collectors simply became interested on their own and then struck out to see what could be found in the way of interesting coins.

Early Collecting Methods

Before 1860, most collectors obtained their coins in one of the three ways. The first was a tried-and-true method still widely seen today. One simply goes through pocket change, looking for old or somehow special pieces. However, the onset of COVID–19 in the late winter of 2019-2020 has put a slight crimp in this method. Increasing numbers of people have turned to credit or debit cards to avoid handling coins or paper money any more than necessary.

The next method, widespread before 1960 and still in force, was to visit a local bank and obtain rolls of a favorite denomination, such as a dime or half dollar. The budding collector then simply examines the roll, pulling the coins of interest, and replacing the empty spaces in the roll with fresh coins.

The last method, also still in use, was to order proof and uncirculated coins directly from the Mint at Philadelphia, though the other mints were no doubt contacted as well. Today, all such sales are handled by the United States Mint, the present name of the old Bureau of the Mint. This method has increasingly become a problem as the Mint seems intent on raising prices to the point that only the really wealthy can afford the more expensive products.

(There is a fourth method of obtaining coins, but this is an internal matter and does not really promote collecting as such. This option is by auction, whereby collectors can obtain needed coins to finish out a set.)

Until 1916, the Philadelphia Mint sold proof coins to collectors and was, in fact, the only source for this material. Some large dealers might order a fair number of silver and minor proof sets, but gold was too expensive to have more than a few pieces on hand for sale.

Prior to 1858, the Mint sold individual proof coins, such as an 1857 half dollar, directly to collectors, but in 1858, Mint Director James Ross Snowden ordered that entire sets of proof coins be ready earlier in the year. Individual pieces could still be purchased, but the point was to cut down the labor involved in dealing with such requests. Today’s numismatic references claim that the 1858 Snowden order was meant to increase proof sales, but this was not the case. It was merely to hold down expenses; no premium was changed on proof coins, and the government lost money when all of the necessary costs were figured.

Proof Coins Prove Change Landscape

Because there were an increasing number of collectors in the late 1850s, the sales of proof coins grew dramatically. In 1859, for example, there were 800 silver proof sets (which included the cent) prepared by the coiner for sale to collectors. Director Snowden realized that the Mint would be losing even more money and instituted a premium; the silver proof set (which included the cent), with a face value of $1.94, was now ticketed at $3.00 plus postage. However, the individual coins had a pro-rata premium, so a set could be purchased at the same total price as single pieces.

However, the new premium prices merely allowed the Mint to break even on the proof coinage and not operate the program at a loss to taxpayers as had been the situation before 1860.

In late 1861, under a new mint director, James Pollock, the system was amended in that full proof sets had to be purchased, whether of silver or gold. This decision worked a hardship on the collector of smaller means, and in 1864 the Mint began selling minor proof sets, which by 1865 consisted of one-cent, three-cent, and five-cent coins. The latter two coins had a copper-nickel alloy. This system remained in effect until 1881, when the Mint permitted individual gold proof coins to be sold for the first time since 1861.

Until the 1910s, little changed in the way that collectors obtained coins. In the early 1920s, the United States Treasury began selling sets of uncirculated coins as one way of replacing proof sets, the striking of which had ended in 1916. In the meantime, there were beginnings of private people promoting numismatics. In the early 1880s, William Von Bergen issued small booklets listing coins known to exist and their values among collectors. By 1900, the expanded versions by Von Bergen were widely known and could perhaps even be called an early forerunner of the current Guide Book of United States Coins, or the Red Book.

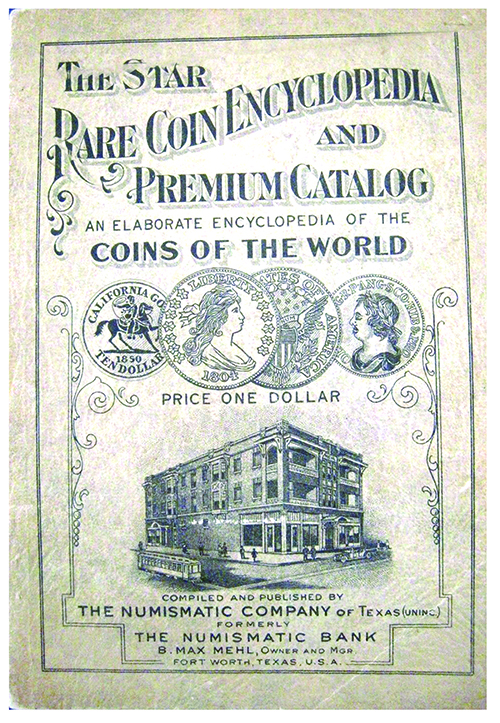

The Von Bergen catalog was widely used in the years immediately following 1900 but gradually lost favor to a very similar book later published by famed Fort Worth (Texas) coin dealer B. Max Mehl. (It was so similar that Mehl’s detractors claimed that he had simply copied the Von Bergen book.)

Pioneers of Identification and Pricing

Mehl’s work, called the Star Rare Coin Encyclopedia, was sold at newsstands around the country and can be called the first true promotional effort for numismatics in the United States. It was very popular in the 1920s and 1930s, and the buying prices enabled Mehl to obtain a large number of rare and valuable U.S. coins. It also proved a useful handbook for the aspiring collector as it gave a good indication of rarity and the kinds of available coins.

Mehl was also well ahead of his time in that he advertised heavily in the major newspapers of that era. If Von Bergen had led the way, B. Max Mehl proved an effective follower and numismatic promoter in the 1920s and 1930s. The Mehl handbook was soon copied in another way by equally famed dealer Wayte Raymond, who published the Standard Catalog of United States Coins beginning in the 1930s; the last edition was under the direction of John Ford, Jr., in the early 1950s. However, the Raymond effort was not promotional in nature but rather served as a high-quality reference for existing collectors.

The most critical item in promoting numismatics after World War II came in 1946 when Whitman Publishing decided to issue a low-cost version of the Raymond catalog. The Guide Book of United States Coins, or Red Book as it is commonly known, proved an instant success and is still the most widely used source for United States coins. Unlike most numismatic books, the Red Book has played a strong dual role. It provided source material for the collector and strongly promoted numismatics by being readily available on newsstands and public libraries.

During the 1950s, a type of coin dealer could be called a promoter of numismatics. These individuals took out newspaper advertisements promoting special issues of coins and coins that were really bullion pieces (such as double eagle) masquerading as collector coins. One of the most prominent of these specialists was Harry Forman of Philadelphia.

In the late 1960s, in close cooperation with John Ford, Jr., Forman began to publish numismatic information that was of value to not only dedicated numismatists but also the public at large. His 1971 book, How You Can Make Big Profits Investing In Coins, was a best-seller by modern standards and drew many non-collectors into the hobby. Even though published 50 years ago, the advice contained in this seminal work is still considered of value by the astute investor.

Forman was something of a “man for all seasons” in that he handled a wide variety of numismatic items. In particular, after silver was no longer used in the circulating coinage, he was a key figure in the roll and bag market and rare and historic coins. Key figures in the numismatic world depended on Harry Forman for up-to-date information in such matters.

Today, there is only one person who has taken on the combined roles of B. Max Mehl and Harry Forman. He is Scott Travers, with his yeoman work in publishing numismatic works for the common person. In addition to numerous TV and radio interviews, he has helped to slow the steady decline in numismatic interest in this country. Travers is but one person, however, and many more are needed.