By R.W. Julian

When beginning collectors find a coin dated in the 1800s or earlier, they automatically assume that was the year it was actually struck, not the year before or the year after.

Unfortunately, this is not always true, even today.

When the 2020 coins are first used by the public, say in January of the new year, most collectors believe that these coins were all struck after January 1. This is generally correct, but on several occasions over the past couple of decades, the mints have occasionally struck coins of the coming year in December. This is done so new circulation coins, as well as bullion pieces, of the given date, can be seen fairly quickly in the marketplace in reasonable numbers.

The advance coins struck in December, however, are not delivered in that year and have to wait until early January to be officially counted as the coinage of that date. This is necessary because of certain legal requirements.

Defining Date Details

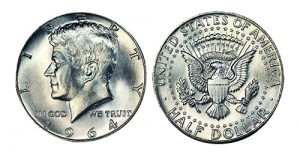

dollars were struck as

late as 1966.

PCGS

Dates on coins have always fascinated collectors, from the very beginning of organized collecting in the 1850s. One of the first dates to attract attention was 1652, as nearly all of the Massachusetts silver coinage of that period carried the 1652 date. One minor issue is dated 1662. At first, numismatists thought that all of the Pine Tree shillings, for example, dated 1652 were actually struck in that year, but it was soon realized that 1652 was a “frozen” date. This means it remained on the coins from 1652 to 1684 when the Boston mint was finally closed.

Because the Massachusetts silver coinage began at a time that the English Civil War was winding down, it has often been assumed that the 1652 date was frozen to avoid problems with the English government. The coinage was technically illegal under British law, but the London authorities paid little attention until the 1670s, and even then nothing was done.

The next coinage executed in this country did not come until after independence had been achieved in 1783. During the 1780s, several states began their own copper coinage, and the Confederation government itself arranged for the private contract coinage of the Fugio cents in 1787.

None of these coins had serious dating problems, and in nearly all cases, a given coin can be assumed to have been struck in the year marked on the coin.

There is one piece struck abroad that somewhat defies the above rule, however. The Washington head cents, carrying the legend “Unity States of America,” are dated 1783, and it was long assumed that the date was accurate for these pieces struck in England. In due course, however, researchers found they had actually been made in about 1820 and back-dated to sell in the United States as small change for the marketplaces.

It is with the beginning of the federal coinage in 1792, that we arrive at the many interesting examples of coins bearing dates that do not exactly correspond to the year of striking. For 1792 and 1793, there are no problems; all coins and patterns bearing those dates were struck in the year stamped on the coins. The year 1794 is another matter entirely, as it marks the first time that coins were struck at the Philadelphia Mint from dies that were out of date.

During 1794, the Mint struck half cents, cents, half dollars and silver dollars, all carrying the correct date of 1794. There were also plans to strike half dimes (five-cent silver coins) during that year, but something went wrong and the plan had to be laid aside for the time being. In February 1795, Chief Coiner Henry Voight was able to begin striking half dimes, but the only dies on hand were dated 1794.

Stack’s Bowers

The 1794 half dime dies gave out in due course and were replaced with those bearing the correct date, 1795. As a result, anyone owning a 1794 half dime has a coin actually struck in February or March of 1795. Most collectors find such information to be very interesting as it makes the coin more historic and worthy of discussion when being displayed.

In fact, the 1794 half dimes were not the only coins struck in 1795 with the wrong date. Only a few thousand half dollars had been produced in 1794, and the dies were still useable when January 1795 arrived. Dies were expensive and time-consuming to make, so the coiner used the 1794 half dollar dies for about 18,000 more coins in early January 1795. Half dollar dies carrying the correct 1795 date were then put in the coining press.

Common Practice With Dies

From 1795 on, it was common to use dies of a preceding date for a few weeks, or even months, into the new year. One such coin that well proves this point is the 1796 quarter dollar, one of the better-known rarities of the early days. Some 252 pieces were delivered by the coiner in early 1797, but the date 1797 does not exist for this denomination.

On the other hand, there are significant mintages shown in the records where no coins are known. One of the best examples is the 1799 coinage of half cents, more than 12,000 pieces; not a single one is known today of this date. In this case, it is known that dies of 1797 were used.

Stack’s Bowers

In fact, the 1797 half cent dies were used even into the opening weeks of 1800. Those owning a 1797 half cent, therefore, cannot be certain of exactly which year saw their coin being made.

A similar situation held for the 1801 half eagle ($5 gold piece) coinage. There were 26,000 pieces struck, but these coins were almost certainly all dated 1800. For this reason, modern catalogs, such as the Guide Book of United States Coins (the Red Book), lump the 1800 and 1801 mintage figures together under the year 1800.

The question of overdates also enters into this discussion though not at the same level. General speaking, an overdate on a coin indicates that the coin was struck during the year placed on the coin.

Truth About the Mysterious 1804

Perhaps the most famous date in early United States numismatics is 1804, which covers the ‘King of American Coins,’ the 1804 silver dollar. In the nineteenth century, many collectors believed that these special coins had actually been struck in 1804 but somehow had been lost at sea or melted for their silver content, leaving only a handful for posterity.

The truth about the 1804 dollars turned out, as the old saying goes, to be stranger than fiction. In 1834, President Andrew Jackson decided that American interests needed a visible presence in the Middle and Far East in order to benefit our growing industrial capacity. A special envoy, Edmund Roberts, was appointed to visit certain nations in that part of the world.

Envoy Roberts suggested that presents be prepared for the rulers of the countries to be visited as this was traditional. Among the items were to be sets of United States coins, and these were duly prepared and placed in special ornate cases in late 1834 and early 1835.

Stack’s Bowers

For reasons that are not entirely clear, Mint Director Samuel ordered that all of the coins mandated by law to be struck were to be included in the special sets. However, neither the silver dollar nor the eagle ($10 gold) had been minted since 1804, and Moore ordered that these old dates be used rather than 1834 or 1835.

What Moore did not know was that the date 1804 had not been used for dollar coins in 1804 although nearly 20,000 had been made. The correct date, however, had been used for the gold eagles coined in 1804. Instead, older dies had been used, probably from 1803 although 1802 or even 1801 is possible.

Because of the mystique that surrounds the 1804 dollars, owning one of the surviving specimens became the hallmark of an outstanding collection. It should be mentioned that there are two kinds of 1804 dollars, originals, and restrikes. Fifteen pieces are known in all, of which eight were struck in 1834 and 1835 while the rest were minted in later years. The dies were destroyed in 1869, however, ending any chances of further specimens being struck. Whatever the source of these coins, if one appears at auction, it is headline news in the numismatic publications of this country.

Mint Report Details

Sometimes the collector will encounter coins for which there is no mint report of having been made. One of the best examples of this is the 1815 half dollar; none was struck in 1815, but the existing pieces were all produced in January 1816. There are, of course, no genuine half dollars dated 1816.

Another example from the same time as the above half dollar is the 1815 cent. Cents were actually struck in late 1815 but dies of 1816 were likely used in advance of being released to the public. Some researchers believe that 1814 dies were instead used, not those of 1816. Cents dated 1815 do exist, but started life as another date, until they fell into the hands of a skilled engraver.

Ira & Larry Goldberg

The 1827 quarter dollar is something of a poor relation to the 1804 dollar. Mint reports indicate that 4,000 pieces were struck in that year, but thinking at present is that dies of 1825 were used. A handful of proof specimens exist and were made for collectors in 1827 and, perhaps, 1828.

At one time, it was thought that the 4,000 figure referred to quarter dollars with that date, but later investigations showed otherwise.

The year 1835 marks something of a watershed in the dating of coins. Before that year, it was standard practice, when necessary, to use out-dated dies as long as they were serviceable. In July 1835, however, Dr. Robert M. Patterson became the director and wanted to place United States coins on a par with the best Europe had to offer. It was the practice of the European mints at that time to use only the current date for their coinages, and the new director put this into practice at the Philadelphia Mint and the branch mints.

There are occasional minor dating problems for other nineteenth-century coins after 1835, but none of them has grabbed collector attention in the same manner as the 1804 dollar. There are always discoveries that might take place, however.

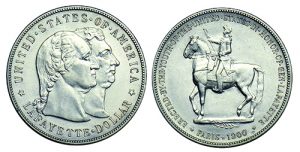

The next significant coin to be considered is the Lafayette silver dollar of 1900. Or is it 1899? The problem arises from the time of striking versus the date that appears on the coin.

There was a national fundraising drive in the United States to erect a statue in Paris in honor of the Marquis de Lafayette, the Frenchman who was one of the key aides to George Washington during the American Revolution. To many Americans, the very name Lafayette symbolized the sacrifices made by France in assuring the victory of the American forces during the Revolutionary War. Without the men and materials supplied by Paris, the outcome could easily have been defeat instead of victory.

As part of the fundraising effort to pay for the Lafayette monument in Paris, Congress authorized a special commemorative silver dollar for sale to the public at $2 each. Chief Engraver Charles Barber considered this coin as one of the most important he had worked on because of the national and international associations.

By late 1899, the dies were finished, and another interesting decision was made by the Mint Bureau in consultation with the Treasury. All of the proposed coins were to be struck on December 14, 1899, the exact 100th anniversary of Washington’s death. Fifty thousand pieces were duly minted on that day from several different obverse and reverse dies; the reason for this was to produce the best quality possible as the coins would be examined both at home and abroad.

Debate Over A Date

The dating of this coin has proven a problem for those who prepare coin catalogs. Should it be called 1899 or 1900? Why 1900? Well, the reverse of the coin has this date on it as the scheduled completion of the Lafayette statue in Paris. It is the opinion of this writer that the commemorative Lafayette dollar ought to be cataloged as 1899 as that was when it was actually struck. The 1900 date was merely the projected date for the monument.

For the 20th century, several of the commemorative half dollars are best described as confusing for their true dates. This curious state of affairs is perhaps best seen in the 1921 Alabama half dollar. It commemorates the 100th anniversary of the admission of Alabama to the Union in 1819, but Congress did not authorize the coin until 1920, and it was not struck until 1921.

A second commemorative half dollar example, among many, would be the Texas issue. The 100th anniversary of statehood was in 1936, but the issue was first struck in 1934 and continued to be produced for collectors until 1938.

The last major dating confusion comes within the lifetimes of older COINage readers. Due to the coin shortages of the early 1960s, there was a date freeze beginning in 1964. It was well into 1966 before the first 1965 coins were finally struck for circulation. There is thus no way, for example, of knowing if a 1964 half dollar was actually struck in that particular year or one of the two following years.

Since the 1960s, there has been little in the way of dating problems though, as noted earlier, some issues were struck in December with next year’s date to allow for an early release to the public. Only time will tell if some change in policy will produce dating questions on future coins of the United States.