By Joshua McMorrow-Hernandez

The moment came with barely the whisper of a maple leaf, but Canada is already marking five years since the issuance of its last circulating one-cent coins. The last penny—a coin that was once a staple in Canada’s commerce—rolled off the presses at the Winnipeg, Manitoba, branch of the Royal Canadian Mint (RCM) on May 4, 2012.

Nine months later, on Feb. 4, 2013, the Mint stopped distributing one-cent coins to financial institutions.

Path of the Canadian Cent

Canada’s one-cent coins have roots going back to 1858, when the then-United Province of Canada was still a British colony. They were struck by the Royal Mint in Great Britain until 1908, when production of Canada’s coinage was moved to Ottawa, Ontario.

The penny was originally issued as a “large” cent measuring 25.4 millimeters in diameter, but it was reduced to 19.05 millimeters in 1920, and it remained that size until its final days. Canadian cents were made almost entirely from copper, as much as 98 percent, until 1996. Following a three-year period (1997-99) during which the cent was 98.4 percent zinc with copper plating, it finished with 94 percent steel and 1.5 percent nickel with copper plating.

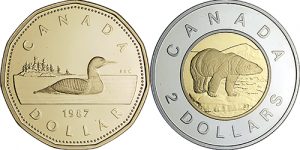

While politicians and hobbyists continue debating the fate of the one-cent coin in the United States, Canada has not struck one in the past five years, and has hummed along economically, socially and numismatically. Never mind that Canada had already replaced its dollar bill in 1987 with the cost-cutting “Loonie” gold-colored one-dollar coins, bearing its iconic eponymous reverse design of a common loon.

It’s a feat the U.S. government has attempted multiple times since 1979 with the release of various small-size dollar coins. Each dollar coin campaign has so far failed, due mainly to public rejection of dollar coins and a general reluctance to forego dollar bills. Could the United States also issue a circulating two-dollar coin, as the Canadians have done since 1996 with its “Toonie”? Given the average American’s resistance to changing our change, that’s probably little more than a pipe dream now.

How does Canada do it? In 2017, five years since the last circulating Canadian one-cent coins were made, hobbyists have the opportunity to gain perspective on what the abolishment of the penny means for Canada, the effects its demise has had on the coin-collecting hobby, and what would happen if the U.S. one-cent coin met a similar fate.

Bidding Farewell to the Canadian Cent

Canadian Broadcasting Corp. (CBC) News ran an “obituary” on Feb. 1, 2013 headlined “Canadian Penny, 1858-2013”. The satirical eulogy even references a cause of death: “The penny’s demise had been anticipated since March 29, 2012, when Federal Finance Minister James Flaherty announced in the budget that his government had decided to phase out the smallest denomination of Canada’s currency.” Eliminating the penny was practical from a fiscal standpoint, as each one-cent coin cost 1.6 cents to produce and distribute.

The obituary, wittily declaring the Canadian penny was “predeceased by the Australian (1911-1964), New Zealand (1940-1989), and Irish (1928-2000) pennies”, added, “the penny will retain its value indefinitely”. Indeed, the Canadian cent retains its legal tender status, as do all of Canada’s discontinued coins.

Yet, the one-cent coin’s presence in circulation is not nearly what it was just a few short years ago. “I haven’t seen any one-cent coins in circulation in years,” remarked New Brunswick, Canada, collector Kevin Day-Thorburn. “Although I’ve found a couple on the ground.”

Day-Thorburn, an executive member of the Royal Canadian Numismatic Association and editor of its electronic publication, NumisNotes, said, “lots of people are definitely hoarding the coins”. Yet, for the pennies remaining in circulation, he has noticed an uneven pattern of redistribution by banks: “I have seen rolls of cents being turned in at the bank, where policy on the handling of these seems to be different from branch to branch.”

Canada’s Currency Act permits individuals to spend up to 25 one-cent coins in any single transaction, with the option to roll up more and turn them in at a bank. “Some banks will give [pennies] back to collectors who ask for them, while others return them to be melted, which, I assume, is what is supposed to happen.” Indeed, the Royal Canadian Mint’s policy on the one-cent coin has been to recycle them as they march in by the armored truckload. Of an estimated 30-plus billion one-cent coins in circulation just after the penny was abolished, 4 billion had already been redeemed by the Mint for recycling less than two years after the last rolled off the presses in Winnipeg.

“The general public seemed very accepting of the elimination of the one-cent coin,” said Day-Thorburn. “Retail shops were made aware that they no longer had to accept the coin from customers if they didn’t want to, but some (very few) stores continued to do so. At the time of the changeover we had our own shop and continued to accept them, but very few people cared about using them. Most of the public just stopped using them cold turkey, so to speak.”

Easy Adaptation in Commerce

These days, it’s become common practice for merchants to round up or down to the nearest nickel, after tax is added. “I have heard some stores that always round up, but I’ve not really noticed,” added Day-Thorburn. “It should also be noted, in my experience, most consumers are using electronic methods of payment now.” Perhaps that has something to do with merchants still charging to the exact cent on purchases involving credit and debit cards.

“Canada has adjusted, economically and numismatically, easily to the elimination of the one-cent coin,” Day-Thorburn observed. “I know of no issues with it. I think there would have been more resistance had we been given a choice, but since it was just announced that the coin’s elimination was happening, it was accepted.”

In September 2016, Day-Thorburn conducted a poll in NumisNotes to see how many readers missed the Canadian one-cent coin. “The results were nearly evenly split, with 52 percent replying ‘no’,” he said. “A couple comments I received were, ‘Let it go.

Coins less than 25 cents [in denomination] have virtually no buying power now.’” Other comments, according to Day-Thorburn, include, “Do I miss the one-cent coin? As a collector, yes, as a consumer, no.”

Day-Thorburn said, “I think, from what I’ve seen, there may be more collectors paying attention to the one-cent coin now, especially the small cent, but it’s not a huge difference.”

Jim McKenzie is a Canadian coin collector and a member of the Saskatoon Coin Club in Saskatchewan, Canada. His observations on Canada’s adaptation to a virtually penniless existence corroborates with Day-Thorburn’s perspective. “Every retail outlet I know of no longer gives out pennies in change, and any they get are sent straight to the bank, then off to the Mint to be melted down. By the middle of 2013, every retailer I know of had stopped spreading them into the public,” he said.

“Economically, I don’t think [eliminating the penny] has had much of an impact,” McKenzie remarked. “For all electronic transactions we still calculate everything to the nearest cent. It’s only cash-in-hand transactions that have been affected. Personally, I don’t miss them in my pocket.”

Missing the One-Cent in the Hobby

Yet, the hobbyist in him still misses the penny. “Numismatically, it’s a shame they are gone.” But he said there is at least one silver lining. “Now, collectors who are obsessed with having one of everything now have an absolutely defined list of Canadian one-cent coins. They can look at that subset of their collections and finally say, ‘There! Done!’”

McKenzie said many of his fellow Canadian collectors still enjoy pennies. “When we have had them for sale at our club auctions, they’ve been a good seller. I would imagine coin club membership applications have risen a bit, and coin stores would see a slight increase in traffic because of people looking for them.”

Meanwhile, countless pennies languish in coin jars across The Great White North.

“Some cashed them in immediately because they were worried about the one-cent coin being demonetized, but after the word spread that they would always be legal tender, the smart ones have kept their jars intact, assuming their values would only increase from now on.”

Those who search their penny jars today may become tomorrow’s collectors, just as thousands of other Canadian coin collectors gravitated toward the hobby after finding old, rare, or valuable pennies in pocket change. With the affordable penny now on the road to extinction as a circulating coin, McKenzie thinks the nickel (Canada’s lowest-denominated circulating coin) may become the next gateway coin for Canada’s next generation of collectors.

“Now that I think about it, the five-cent coin today has about the same buying power as a one-cent coin did when I was a child back in the 1960s,” he said. “In the long run, I don’t think it has much of a detrimental impact on budget-conscious young collectors.

“I think it has actually added a level of excitement for new collectors, because when they do see [pennies] in a club meeting or coin store, they’re intrigued by them.”

Opening Doors to New Coin Interests

Canadian collector Gerald Sander said his nation’s transition away from using the cent has gone “very smoothly” and that the penny is “not missed”. He usually encounters pennies only in collections these days. “I think it will take a while for pennies to become hard to find. Look at how easy it is to get silver coins after all these years of melting them.” Single one-cent coins might not be popular according to Sander’s observations, but there is at least one area of penny collecting that he thinks is hot: “I think people are collecting uncirculated rolls for sure.”

Patrons at Gatewest Coin Limited, an official distributor of Royal Canadian Mint coins and bullion products in Winnipeg, Manitoba, still enjoy buying Canadian cents.

However, General Manager Jasmine Allen hasn’t noticed any significant increases in demand for pennies at her store. “I wouldn’t expect there to be a demand increase for a few decades, seeing as the collectors joining the market now are still very familiar with pennies, having handled them most of their lives,” she said. “Canadian cents are not yet a novelty item that you can teach your kids about and get any interest.” She remarked that prices on key and semi-key dates, such as the 1884 large cent and all small cents dated from 1922-27 inclusive, are similar to what they were a few years ago. “There is, however, at least some market for any pennies dated from the 1980s and earlier.”

Any discussion in American numismatic circles of Canada’s recent experience with its one-cent coin naturally evolves into discourse on the situation involving the U.S. penny. Longtime Irvine, California, coin dealer Charmy Harker, who is widely known as “The Penny Lady”, said interest in collecting pennies would jump if the United States ever halted production of the one-cent coin.

“If they decide to stop issuing the U.S. one-cent and people start turning in pennies to the banks, I believe we may see a boost in collector interest, both from existing penny collectors and those interested in starting a collection of pennies,” she remarked. “It’s possible the value of pre-1982 copper pennies would start to increase as more and more of them are removed from the market, both by turning them in to the banks or by collectors and hoarders.”

Harker is unsure whether the federal ban currently in place against melting U.S. one-cent coins would subsequently be lifted if production of the coin ceased. “At some point they will have to be melted. Whether or not the melting ban is lifted, I think people will hoard pre-1982 pennies more than ever.”

Seeking Alternative Options

Harker’s bigger concern isn’t whether or not the penny-melting ban would expire should production of the one-cent coin run its course. Rather, she is worried about what the loss of the coin might mean to numismatics. “The penny is the foundation to most young people getting into collecting coins, even to this day. If the penny is no longer minted, it’s very possible their value will increase, which will make it more expensive and thus more difficult for new young collectors to begin collecting.”

The Penny Lady, a member of several leading coin organizations and president of Women in Numismatics, thinks a compromise could come in the form of striking one-cent coins from a cheaper metal. “I hope they find a new, more economical composition [for] the penny rather than end production altogether.”

According to a recent Wall Street Journal article, the cost of making a one-cent coin increased in 2016 to 1.5 cents, up from 1.43 cents in 2015, but down from 1.66 cents in 2014. While production costs for the one-cent coin fluctuate from year to year, the denomination has become increasingly more expensive to produce since the 1970s, despite a major compositional makeover in 1982.

When copper prices spiked in the early 1970s, United States Treasury officials experimented with making one-cent coins from cheaper materials, such as aluminum.

By 1982, the Treasury finalized plans for a cost-saving copper-plated zinc composition, which is still used today for circulating Lincoln cents and most numismatic one-cent coins, though at an expense now exceeding the face value of each penny. Analysts say the Mint could save tens of millions of dollars each year if the penny was scrapped.

Former U.S. representative Jim Kolbe, a Republican from Arizona, introduced legislation in 1990, 2001 and 2006 to eliminate the one-cent coin. In 2008, former U.S. representative Zach Space, a Democrat from Ohio, proposed replacing the compositions of both the one-cent and five-cent coin (the latter costing 6.32 cents each to produce in 2017) with cheaper metals, including steel.

Canada’s Move Sparks Consideration By Others

When interviewed for a February 2016 COINage article on the future of the one-cent coin and nickel, Space said his 2008 bill, H.R.5512, faced numerous obstacles. “There were a number of competing interests. For example, manufacturing facilities that rely on the U.S. Mint business, such as those producing [plachets] for pennies and nickels, could be threatened by the legislation,” he said. “I received some pushback from numismatists who were concerned about the potential loss of rare pennies as part of the process.”

Meanwhile, a slim majority of public still supports keeping the penny. A January 2014 YouGov/Huffington Post survey showed that 51 percent of Americans wish to keep the penny, while only 34 percent want to eliminate it.

It doesn’t take a seasoned numismatist or government expert to realize the differences in experiences with this issue on either side of the United States-Canada border are like comparing night and day. Yet, Democratic Michigan state Sen. Steven Bieda, a longtime coin collector who has served in politics since 2003, is precisely the type of individual who can provide deeper insight into this complex narrative.

“I suspect the difference in the population of the two countries, as well as the various groups lobbying for the retention of the United States one-cent coin has made the political climate more difficult for U.S. policymakers to act,” Bieda said. The senator, who in 1992 provided the reverse design for the United States Olympic commemorative half dollar and serves as legal counsel for the Central States Numismatic Society, witnessed bureaucratic backlash against penny reforms in the past.

In the early 1980s, the Copper & Brass Fabricators Council sued the Treasury when officials decided to eliminate most of the copper from the one-cent coin. These days, it’s zinc lobbyists who rally against bills axing the cent.

According to Bieda, “In addition to the copper-zinc lobby, consumer groups, as well as those who lobby for the economically disadvantaged, have collectively argued against the elimination of the cent with concerns expressed about inflation.” He believes that eliminating the one-cent coin would give a negative economic impression.

Politics’ Relation to Pennies

“For United States politicians, eliminating the one-cent coin carries with it an admission of the slipping strength and value of the U.S. dollar, something neither the Democrats nor the Republicans want to be saddled with,” Bieda acknowledged. “For a congressman running for reelection, having a commercial that alleged prices ‘got rounded up’ because he eliminated the one-cent coin is also likely a factor.”

Bieda, a prolific numismatic journalist, wrote an article about the elimination of Canadian one-cent coins in the November 2012 issue of the American Numismatic Association’s monthly publication The Numismatist. “The decision to cease manufacture of Canada’s lowest denomination was not made overnight,” Bieda wrote. “On Dec. 14, 2010, Parliament’s standing Senate Committee on National Finance released a report calling for the Royal Canadian Mint to cease production of the one-cent coin and remove it from circulation.”

On March 29, 2012, the federal government released a budget statement reporting the cost of producing each one-cent coin was 1.6 cents and subsequently announced the elimination of the penny. The last one-cent coin was made just a few weeks later and, just like that, the penny was done.

“Canada provides a good model on how we can abolish the one-cent coin and not hurt consumers,” Bieda stated. “I love one-cent coins, but economically it doesn’t make sense to make cents anymore.”