Editor’s Note: This is the first of a two-part series of articles about the Philadelphia Mint. Part I focuses on the beginning of the United States Mint through the first 150 years of its operation. Enjoy Part II of this series >>>

By David T. Alexander

The year 2018 marks the Philadelphia Mint’s 226th year of robust service to the American people. A survey of the performance of this Mint, America’s first, reveals that this nation’s coinage has followed what biologists call a “circle of life.” As decades turn to centuries, U.S. coinage has travelled a lengthy, winding road of design from the first pioneer efforts of the 1790s through the ultra-modern artistry of the 20th century and beyond.

A glance at some recent additions to U.S. coinage shows a subtle tendency to return to some of the finest designs of earlier years. Consider the gold and silver bullion coins introduced since 1986. The 1907 Augustus Saint-Gaudens gold double eagle obverse with its striding Liberty was subtly modified for the gold $100 bullion piece and its fractions and joined to a new Family of Eagles reverse by artist Miley Busiek. After experiencing some ups and downs in sales over the years, the 2018-dated pieces have shown an exciting increase in popularity and public sales.

Much the same thing is happening with the stately Walking Liberty silver bullion coin whose obverse was created by Adolph Alexander Weinman in 1916. Joined with a modern treatment of America’s national eagle, this one-ounce .999 silver coin with its denomination of $1 has shown increasing market strength that has joined its undeniable beauty and visual appeal.

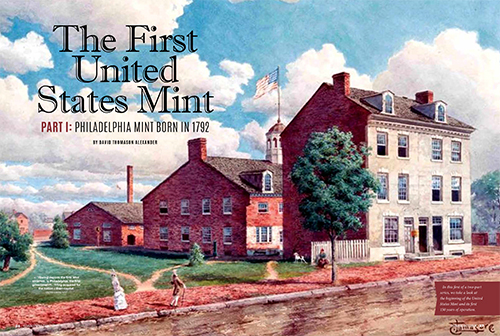

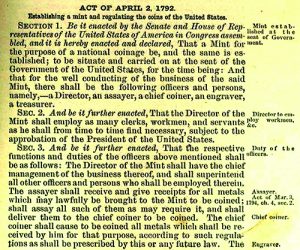

The United States Mint at Philadelphia was created by Act of Congress of April 2, 1792, and remains today the principal producer of this country’s coinage. Philadelphia was the capital of the U.S. when the Mint was created, and the first Mint building was the first structure acquired for the use of the government of the young nation.

Elaborate rules and regulations for Mint operation were drawn up, along with a hierarchy of Mint officers and technicians. The first director was astronomer, clock and precision instrument maker, surveyor, and mathematician David Rittenhouse (1732-1796). His hand was apparent everywhere, including on the elaborately carved wooden back of the presiding officer’s chair in the Constitutional Convention with its high-relief glowing sun.

Regarding this emblem, the ever-observant Benjamin Franklin remarked with marvelous optimism, “It is a rising, not a setting sun!” Although old and in failing health, Rittenhouse was able to assemble a new Mint staff and keep comparative peace among the massive egos who comprised it.

(Photo courtesy American Numismatic Association)

He diplomatically handled a penny-pinching Congress and successfully launched gold, silver, and copper coinage despite every kind of shortage and regulations that demanded staggering cash bonds for those handling precious metals. His worldwide scientific reputation was summarized in the inscription on the 1871 Rittenhouse memorial medal of the Philadelphia Mint: “He belonged to the whole human race.”

Copper coinage began using such horse-driven machinery as could be obtained or built in Philadelphia. Die steel was critically scarce, bullion for silver and gold was irregularly supplied, and acceptable copper for cent coinage was always a source of anxiety. Skilled American workmen were hard to find and harder to replace after the annual ravages of yellow fever in Philadelphia’s near-tropical summers.

An ongoing problem was educating ill-informed and hostile congressmen, whose calls for the Mint’s abolition and for adoption of contract coinage bubbled in the background. Contract coinages were an ongoing concern in the booming British industrial center of Birmingham, site of entrepreneur Matthew Boulton’s thriving Soho Mint. Some copper blanks for large cents were supplied by Boulton, but their shipments were endangered during the naval war between Britain and revolutionary France.

Coin design attracted some public debate throughout the 19th century, thanks in part to the concept of “uniform design.” Both government and public feared that design change for copper, silver, and gold pieces would somehow encourage counterfeiting. Thus, dowdy Liberty busts dominated half dime, dime, quarter, and half dollar obverses for decades. The 1807 and later silver bore an inelegant and frumpy Liberty lampooned as the likeness of engraver “John Reich’s fat German mistress.”

Pennsylvania-born designer Christian Gobrecht contributed the Liberty Seated obverses that dominated silver from the half dimes through half dollars from the 1830s into the 1890s, and the same designer’s Liberty busts appeared on $2-1/2, $5, and $10 coins for decades. His elegant flying eagle was created for a few circulating silver dollars and patterns of 1836 but never made it to lower denomination silver.

By the 1830s, directors of the Mint had achieved considerable stature in the federal hierarchy, and the Mint itself was remarkably stable. The institution remained in Philadelphia after nearly all federal institutions relocated to the new capital of Washington, D.C. Eventually, the highest Mint officers were relocated to Washington, where they remain today, but coin production stayed in its original home.

The elegant second Mint building boasted a distinctive pillared portico and was dominated by a tall smokestack of the refining department, as seen on the 79-mm portrait medal of Director James Ross Snowden by Anthony C. Paquet with its boast, “RENDERED FIRE PROOF 1856.” This building remained in active use until 1901.

The massive third Mint was opened in 1901 until replaced by the fourth Mint until 1969.

Westward expansion in the 19th century necessitated creation of branch Mints in six distant locales between 1838 and 1906, and introduced the first mintmarks: “C” for Charlotte, North Carolina (1838); “O” for New Orleans, Louisiana (1838); “D” for Dahlonega, Georgia (1838); “S” for San Francisco, California (1854):

“CC” for Carson City, Nevada, (1870); and “D” for Denver, Colorado, 1906. The United States Bullion Depository at West Point, New York, evolved into a Mint de facto and finally de jure in the late 20th century; its mintmark is “W.”

All branch Mints were subordinate to Philadelphia, and all the southern Mints except New Orleans were casualties of the Civil War. It is interesting to recall that Appalachia was site of the nation’s first gold rush, and the cry “There’s gold in them thar hills” was a call for prospectors and miners to remain in the South rather than join the frenzied rush to the Wild West.

A new element entered the picture by 1857: coin collectors stimulated by the announcement that the old large cents and half cents were being abandoned in favor of more convenient, smaller copper-nickel coins. Scores of avid collectors now scurried to assemble date runs of large cents, many seeking coins dated 1815, unaware that none had been struck thanks to a fire within the Mint.

An adversarial relationship arose between the Mint and collectors, stimulated by official hanky-panky in production and clandestine sale of pattern coins, illicit restrikes of earlier issues, and the murky background of the famous 1804 silver dollar. Auction catalogs and coin dealer house organs fed the fire. W. Elliot Woodward famously described the ouroboros (snake with its tail in its mouth, symbol of eternity) on Mint Director Patterson’s medal as “an excellent likeness of his [Patterson’s] favorite snake.”

Obtaining the services of talented engravers remained a problem. James Barton Longacre was a Pennsylvania engraver of bank notes and calico rolls. His coin designs featured female heads with long and meticulous noses for his gold $1 and $3 obverses and later copper-nickel cents, which modern research has shown were a family trait of his female relatives.

British-born William Barber (1807-1869) and his son Charles E. Barber (1840-1917) arrived in the U.S. in 1852. William became Chief Engraver in succession to Longacre and served in this capacity until his death in 1869, when Charles succeeded him. The Barbers effectively controlled the designing and engraving departments and worked mightily to ensure their dominance as long as they could.

Mint Director Dr. Henry R. Linderman (1825-1879) was a figure of international stature and directed the Mint in 1867-1869 and 1873-1878. He quickly found dealing with the Barbers more than he could handle. Aware of the continent-sized expansion of silver production underway in the West, he foresaw the urgent need for a new standard silver dollar and advocated creation of the Trade dollar for export to the China trade.

(Photo courtesy the United States Mint)

In a maneuver more suggestive of a James Bond novel than that of the staid civil service, Linderman sought a new Mint engraver overseas without alerting the Barbers. He found George Thomas Morgan (1845-1925), graduate of art schools in Birmingham and South Kensington, London, with some experience in the British Royal Mint. An accomplished medalist, Morgan was recruited as assistant engraver for six months and sailed for Philadelphia.

Presenting himself at the Mint, Morgan met undisguised hostility from the Barbers. Unable to block his employment, they placed every possible obstacle in his path, including denying him work space within the Mint. A patient and cheerful soul, Morgan promptly had heavy machinery transported to his boarding house, managed by a friendly widow with long-standing Mint connections.

Morgan was eventually relocated within the Mint. A skilled medalist who designed many handsome patterns for US coinage, his best-known work remains the standard silver dollar struck 1878-1921. Massive silver purchases mandated by Congress were designed to provide an artificial safety net for silver prices, and the law stipulated that the purchased metal had to be coined only into silver dollars.

The coins struck each year remained heavily on the hands of the Treasury as silver prices dropped lower and lower. Now worth less than face value, the dollar’s greatest use was as backing for Silver Certificates. The mountains of canvas bags of dollars remained in dead storage for generations to come.

A new element appeared in 1891 with organization of the American Numismatic Association (ANA) as a national organization of coin collectors. The project of Dr. George Francis Heath of Monroe, Michigan, ANA experienced several years of initial floundering before setting on its course as representative of the nation’s collectors.

The Philadelphia Mint’s placid routines were disturbed in the early 1890s. Ongoing criticism of the static Liberty Seated coinage led the Mint to hold a contest for new coin designs. This competition was announced in haste and was open to very few artists. Insufficient time was allowed for design preparation and wholly inadequate remuneration was provided to participating sculptors. Charles Barber soon proclaimed it a failure that proved the impossibility of working with outside sculptors and promptly designed the new dime, quarter, and half dollars himself.

As significant was the battle over medals and coins for the great World’s Columbian Exposition set for 1892-1893 in Chicago. Numismatic developments at the fair set the stage for so many events to come that they deserve a careful review. Columbian medals and coins were closely associated with America’s greatest living sculptor, Augustus Saint-Gaudens, who created the massive 76.5 mm medals presented to exhibitors at fair.

Their obverse bore a dramatic scene of Columbus’ landing on San Salvador. The planned

(Photo courtesy United States Mint)

reverse featured a nude youth holding a torch and award scroll for awardee’s names. Before the design was finalized, an infiltrator got access to the drawings, and an operative of the firm that supplied leather transmission belts to the Mint created a lewd parody for distribution to influential individuals working on the fair.

During the resultant uproar ,the ever-ready Barber blithely substituted his own unimaginative reverse design featuring large rectangular tablet resting on a squashed Columbus ship. No one troubled to inform the unsuspecting Saint-Gaudens of this dramatic design change and he stormed off, vowing never to work for the Mint again.

Commemorative half dollars and quarters were struck for the exposition amid controversy over pricing. The public of 1892 found it inconceivable that Americans should be asked to pay $1 for a coin bearing the denomination half dollar. Later, those who paid their dollar looked on helplessly as banks holding thousands of the coins simply dumped them onto the public at face value as the fair ended amid the economic disruption of the Panic of ’93.

The Columbian quarter was issued in the name of the Board of Lady Managers, a body created in deference to the early feminist participation in the expo. Artist Caroline Peddle created the first design, but Barber nimbly substituted his own design based on a bust of Columbus’ patron, Queen Isabel of Castile, and a female kneeling with distaff that suggested the anti-slavery tokens of the earlier 19th century.

These medals and coins cast a long shadow over the Mint’s operations of 1900-1940, beginning with Barber’s 1900 Lafayette dollar, which blatantly copied Peter L. Krider’s 1881 Yorktown Surrender Medal. From 1903 forward, commemorative half dollars and gold denominations burst onto the national coinage scene, commemorating such world’s fairs as the Lewis and Clark and Louisiana Purchase Expositions.

As this review of the Philadelphia Mint’s first 150 years draws to a close, we offer this video segment from a 1940 U.S. government film recounting part of the minting process. Enjoy…